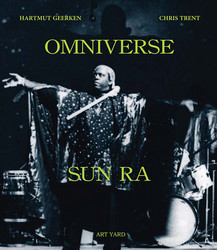

Sun Ra

The Complete Remastered Recordings on Black Saint & Soul Note (5CD Box)

Cam Jazz reissue the complete Black Saint and Soul Note works of Cecil Taylor in hisexemplary series of boxed sets dedicated to the catalogues of the legendary Italian labels. This set contains four albums in slipcases with original album artwork, housed in a sturdy box.

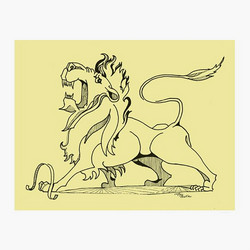

The window afforded into the artistry of pianist Cecil Taylor by this new CAMJazz collection, like all of that label’s Black Saint/Soul Note reissue sets, is not that of a curated collection, greatest hits package or introductory sample in any way except that it reflects Giovanni Bonandrini’s generally excellent tastes and talent for running a label. But it still allows for a fairly representative peek at the work of one of the masters of contemporary jazz and it comes at a more than reasonable price point as well. The four titles included here (spread across five compact discs) make for a wonderful cross section of Taylor’s work, even if the releases only reflect seven years of a recording career which has carried over five decades of counting. The first selection is no doubt the one of greatest historical interest. Historic Concerts is a 1979 meeting with the legendary drummer Max Roach, occupying two of the set’s CDs. After a five-minute solo from each, the duo hunkers down together for an explosive exchange. It’s a fascinating session, almost a competition in a way, with each man seemingly determined to outrun the other. While such footraces don’t always result in the greatest good, Taylor and Roach are both on their toes and the tension is propulsive. The second disc is filled out (as was the original release) by a post-game radio profile, which includes interviews with each of the artists. Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants) is a 1984 large ensemble record similar in feel to his Cecil Taylor Unit and 3 Phasis, which is to say it works in waves of energy built on undulating musical phrases unfailingly bearing Taylor’s imprint. The 11-piece ensemble is seven horns strong (Enrico Rava, Tomasz Stanko, Jimmy Lyons, Frank Wright, John Tchical, Gunter Hampel and Karen Borca) with bassist William Parker and the paired drummers Rashid Bakr and Andre Martinez but Taylor keeps a remarkable hold over the forceful gathering. All of the players are also credited with vocals and the album includes a wonderful group chant piece very much in keeping with the vocals Taylor would explore to greater extents in later years. If this set is looked at as a primer (and it makes a good one, even if that’s not how it came to pass), it would have to include a solo set. For Olim, the one featured here, is a fine such offering. Taylor is at his most enigmatic when he’s alone onstage and this concert – recorded in Berlin in 1986 – is an excellent example, a nicely diverse set of eight pieces. Arguing one Taylor solo recording against another is a complex proposition. The 1981 release Garden would have to be considered one of his best, but For Olim wouldn’t rank far behind. For Olim was recorded at the 1986 Workshop Freie Musik in Berlin and recordings from two other Taylor sets during that festival were paired to make the 1987 release Olu Iwa, which stands out as one of the finest titles in Taylor’s expansive discography. At 27 minutes, “Olu Iwa (Lord of Character)” is the shorter of the two cuts on the disc. It’s a beautiful study for what could almost be called a percussion quartet. It seems to explode Taylor’s piano playing (which has been described as “88 tuned drums”) onto a group setting, with William Parker on bass, Steve McCall on drums and Thurman Barker contributing beautiful marimba and additional percussion. It’s a sublime piece, with the interplay between Barker and Taylor especially pronounced. The next day, Taylor added three horns (saxophonists Peter Brötzmann and Frank Wright and trombonist Earl McIntyre) to the quartet, arriving at the version of his Unit heard on the 48-minute “Be Ee Ba Nganga Ban’a Eee!”. Here again Taylor harnesses the energy of free improvisation while keeping structure and retaining his own indelible stamp. While it’s more incendiary than the quartet piece, the horns seem at certain points to come in as a section. It’s moments like these, the likes of which occur throughout the collection, that show there’s more method to his madness than for which he is often credited. And to his genius as well.