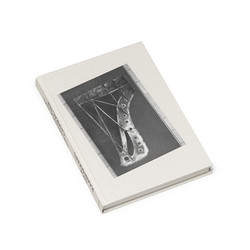

Victor Szabo

Turn On, Tune In, Drift Off: Ambient Music's Psychedelic Past

** 376 Pages, soft cover ** Turn On, Tune In, Drift Off: Ambient Music's Psychedelic Past rethinks the history and socioaesthetics of ambient music as a popular genre with roots in the psychedelic countercultures of the late twentieth century. Victor Szabo reveals how anglophone audio producers and DJs between the mid-1960s and century's end commodified drone- and loop-based records as "ambient audio": slow, spare, spacious audio sold as artful personal media for creating atmosphere, fostering contemplation, transforming awareness, and stilling the body. The book takes a trip through landmark ambient audio productions and related discourses, including marketing rhetoric, artist manifestos and interviews, and music criticism, that during this time plotted the conventions of what became known as ambient music. These productions include nature sounds records, experimental avant-garde pieces, "space music" radio, psychedelic and cosmic rock albums, electronic dance music compilations, and of course, explicitly "ambient" music, all of which popularized ambient audio through vivid atmospheric concepts.

In paying special attention to the sound of ambient audio; to ambient audio's relationship with the psychedelic, New Age, and rave countercultures of the US and UK; and to the coincident evolution of therapeutic audio and "head music" across alternative media and independent music markets, this history resituates ambient music as a hip highbrow framing and stylization of ongoing practices in crafting audio to alter consciousness, comportment, and mood. In so doing, Turn On, Tune In, Drift Off illuminates the social and aesthetic rifts and alliances informing one of today's most popular musical experimentalisms.

“[Certain] music, if you put it on, will keep [listeners] in present time. It wasn’t always called new age music, it could be called trance, mood music, or atmospheric music. Sometimes jazz can do that for somebody,” musician Laraaji tells author Victor Szabo, describing the new age genre in an interview for the latter’s deep history of ambient music. “But music that has a continual drone, and that expresses a fluidity, and that allows for the listener to be present with their breathing, and to be in present time, and to drift away from mundane thoughts, and to feel an emotional sense of connection to the universe, or to the all-that-is – to me, that’s getting into nowness.”

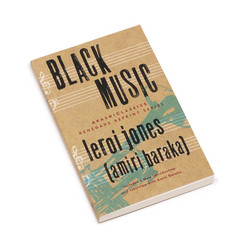

And though this passage appears late in Turn On, Tune In, Drift Off, it might double as a mission statement for the book and the genres it’s explicitly about: new age, ambient and EDM ambient, but also the genres that informed and, positively or pejoratively, inspired them into being – easy listening, psychedelic rock, classical music, jazz and New York minimalism. Szabo, the Elliott Assistant Professor of Music at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, sifts through the myths, narratives and counter-narratives surrounding soothing post-Muzak sonics like an obsessed paleontologist; a selected discography appendix namechecks the first Warp Records Artificial Intelligence compilation, Ana Roxanne, The Orb, James Ferraro, Wendy Carlos and Miles Davis.

Founded in 1973 and hosted by Stephen ‘Timotheo’ Hill and the late Anna ‘Annamystic’ Turner, the nomadic Hearts Of Space radio show was instrumental in popularising diffuse and consciousness-expanding music. Szabo pores over the programme’s musically omnivorous playlists, which often ran for hours, heavy on world music and complete LP sides. An early slogan: “Slow music for fast times”.

The divide between new age and ambient – two sides of the same coin – reveals itself quickly in this telling. New age – exemplified by Tony Scott’s 1964 feathery Music For Zen Meditation, Paul Horn’s 1968 modal flute opus Inside and Stephen Halpern’s 1975 synth float Spectrum Suite – arrived first, emerging as an offshoot of “the material culture around psychedelic experience, alternative spirituality, and holistic health that was rooted in the California counterculture”, Szabo writes. New age, employing nature sounds, mellow vibes and orientalist elements in the purposeful service of sonic anaesthesia, drifted from its granola origins into a sort of yuppie wallpaper. By the 1980s, the genre was widely successful commercially and often derided, by critical organs, as vacuous product.

Concepts introduced by composers Erik Satie and John Cage would inform ambient, a term coined by former Roxy Music member Brian Eno in the mid-70s as he recorded and produced a quartet of LPs (two solo, one with Harold Budd, and another with Laaraji) predicated on unorthodox processes, studio-enabled happenstance and Oblique Strategies. Critically respected if not universally embraced, ambient was pop somnolence as Fine Art, subconscious and beautiful and quietly adventurous, in opposition to what were perceived as minimalism’s dull pretensions. Szabo dedicates a long, probing chapter to Eno’s ambient productions and, in considering Ambient 1: Music For Airports, locates what set the genre apart from new age: ambivalence and doubt.

Ambient found a fresh new context as the 80s gave way to the 90s and 2000s, and EDM culture exploded. It is “shorthand for the music associated with chill-out rooms and areas, which become semiregular features of underground clubs and raves in the United Kingdom,” Szabo writes. “Parties more devoted to chilling than dancing will also emerge, begetting a bohemian electronic music scene driven by young DJs’ transgeneric musical curiosity.”

Laraaji.