In late 1977, Wendy Carlos and her friend and producer Rachel Elkind started looking for the right journalist to tell her story. During the nine years since the pair’s creation of the million-selling Moog-powered phenomenon Switched-On Bach, Carlos had retreated from public life, fearful that her contemporaneous gender transition would overshadow the achievements of the album and its successors. Feeling that the time was now right for disclosure, they made tentative contact with Arthur Bell, the New York gay rights activist whose journalistic debut had been an account of the Stonewall riots.

Although largely sympathetic and upbeat in tone, the resulting feature as it appeared in the May 1979 edition of Playboy magazine greatly dismayed Carlos. Having arrived at interview sessions bearing a sheaf of her own questions about her music and artistic philosophy, she discovered that Bell and Playboy’s editors instead judged readers’ interest to lie mainly in hearing as many details – psychological, sexual and medical – of Carlos’s transition as possible. “I think I would feel happy if a reaction to this interview were a yawn,” she said near the conclusion, after answering Bell’s questions with patience, wit and more candour than perhaps was wise. “I mean, who cares?” Clearly the world had not moved on as much as she had hoped.

The question of how much anyone can control their own narrative runs throughout Amanda Sewell’s careful but by necessity constrained account of Carlos’s life and career. Now 80, with her catalogue out of print, her music rapidly removed from YouTube and her website not updated since 2009, Carlos declined to participate in its writing, as did all still-living friends and former collaborators. Ironically, Bell’s Playboy interview and his extensive unpublished notes serve as a key biographical source in Carlos’s absence. Despite the distance from her subject, Sewell – a musicologist and the music director of Michigan’s Interlochen Public Radio – successfully pulls together a balanced portrait that acknowledges Carlos’s unavoidable cultural status as both a pioneer of electronic music and its most famous transgender woman, while also affording due recognition to her sonic accomplishments.

The latter certainly are impressive. When not experimenting with DIY quadrophonic sound in her parents’ basement, retuning their piano to self-invented systems or recording Pierre Henryinspired musique concrète, the teenage Carlos wrote algorithms instructing 1950s computers to harmonise in the style of Bach. Finding her niche studying both music and physics at Brown University, she then joined the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, working with its founder Vladimir Ussachevsky and composing pieces for tape with live musicians.

While working as a recording engineer and freelance sound designer she met Robert Moog, becoming one of his earliest and most demanding customers. Moog’s own archives allow Sewell to detail how he strove to customise his modular units to meet Carlos’s yearnings for a fully expressive instrument. In return, Carlos gave him first a demonstration record he could use to wow other potential purchasers, then Switched-On Bach, a more persuasive display of the Moog synthesizer’s abilities than he could ever have imagined.

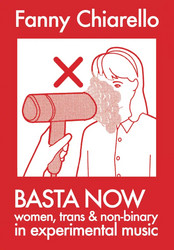

Touching upon similar territory to Dave Tompkins’s vocoder history How To Wreck A Nice Beach, University of California academic Roshanak Kheshti’s contribution to Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series places Switched-On Bach at the nexus of Cold War technology, electronic music’s role as postcolonial propaganda and the social and political ruptures of 1968. Both she and Sewell identify Carlos as pivotal in humanising the Moog, bringing its sound from laboratories into living rooms. The album wasn’t the first to be made using a voltage-controlled synthesizer, coming the year after Morton Subotnik’s Silver Apples Of The Moon. But the painstaking sculpting of every note’s parameters before layering monophonic lines into Bach’s rapturous polyphony lent Carlos’s performance a sensitivity that she herself, writing in Moog’s Electronic Music Review magazine, criticised Subotnik’s Buchla masterwork for lacking.

For Sewell, Switched-On Bach creates an auditory paradox: “How can something be so mechanical and so human at the same time?” For Kheshti, the disparity is temporal: “It signals an elsewhere, another time that seems to beckon the listener into timbres and colours juxtaposed against Bach’s Baroque compositions, which result in a creative tension that resolves in kaleidoscopic colour in the listener’s mind.”

The mainstream success of Switched-On Bach couldn’t have come at a worse time for Carlos, who was deeply distressed whenever she had to appear as the Walter Carlos the public and media associated with her hit album. Beyond immediate fears for her physical safety, she feared tainting the Moog’s newfound status as musicianly tool rather than sci-fi novelty with the sensationalism that would inevitably accompany news of her gender. Yet Sewell describes how the ensuing decade of isolation also hampered Carlos’s career, preventing her from enjoying collaborations and opportunities that would otherwise have been at her fingertips.

Nevertheless, she continued to innovate: Switched-On Bach’s various sequels may have been commercial label pleasers but they allowed further refinement of its mutated orchestral timbres. Elsewhere, she made the vocoder the unmistakable voice of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and blended synthesised nature sounds with field recording on 1972’s Sonic Seasonings. If, as Sewell suggests, the digital synthesis of her 1986 album Beauty In The Beast now sounds dated, then its intricate tuning systems and acoustically impossible instruments still subvert listeners’ expectations.

Sewell is rightly critical of those writers who ignore Carlos’s assertion that her gender identity isn’t inherent in her music, citing examples ranging from cliched tropes of synthesis and transcendence to one particularly crass analogy of the classical canon undergoing “radical reassignment surgery”. Initially Kheshti, too, appears to skirt dangerously close to this line. But by invoking Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, the concept of synthgender and Carlos’s own online adoption of the claim that she is “the original synth”, her focus emerges less as Carlos’s flesh and blood experience than the enduring and binary-collapsing cultural significance of her music.

It’s possible that neither of these two books’ authors will ever discover how their interpretations are received by Carlos, who has once again retreated back into privacy. That said, it’s tempting to envisage her stepping forward for a late-life victory lap, winning new fans with a catalogue reissued for lossless download, choosing select channels to share the stories she wants to and collaborating with new generations of likeminded musicians. While the world still hasn’t moved on in many ways, in others she may be pleasantly surprised.