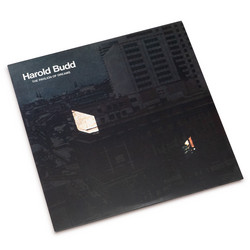

Harold Budd

Wind In Lonely Fences 1970 - 2011

Harold Budd's music exists in that misty place between ambient, new age, and minimalist composition, where everything is gentle and nothing lasts for long. Over the past 40-plus years, he's released about 30 albums. Some are solo, some are collaborative; some are studio and some are live; some are improvised and some are structured. He famously worked with Brian Eno on the second of Eno's landmark "Ambient" series (Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror), and less famously made an album with the Scottish dream-pop band the Cocteau Twins, neither of which have any immediate common ground other than the fact that Harold Budd plays keyboard on them.

Despite the variety of Budd's collaborations and circumstances, his music has always had a quietly recognizable style: intimate and intuitive; fragile but warm; seductive but just a little bit mysterious, like the soft tinkling of a presence in the next room. (In a 2005 interview with the UK paper the Independent, he joked that his music tended to feel slow and searching because he usually recorded it drunk.)

Wind in Lonely Fences is a 2xCD retrospective compiled by All Saints Records and released alongside three vinyl reissues of older Budd albums (The Serpent (in Quicksilver), Abandoned Cities, and Through the Hill) and a seven-album box set called Buddbox. I'm writing about Wind here not only because it's the most convenient inroad to Budd's career, but because it's an ambitious project in its own right: with as many albums as Budd has to choose from and no responsibility to things like radio hits, the job of the compiler becomes an unusually creative one.

Starting with 1970's "The Oak of the Golden Dreams", Wind moves chronologically, ending with a track from his 2011 album In the Mist. Progression is obvious, especially early on. "Dreams", which was improvised on an old Buchla modular synth, has more in common with the dense ragas of Terry Riley than anything Budd composed in the 80s, and even 1978's "Bismillahi 'Rrahman 'Rrahim"—from one of my favorite Budd albums, The Pavilion of Dreams—shows a willingness to indulge in vast, almost jazzy pieces of music that he'd give up within a few years. (A sap at heart, I wilt at the sound of an erotically played saxophone.)

Budd's music got smaller and more peaceful, but also more opaque, culminating in the work he's best known for: The Plateaux of Mirror and the Pearl (also with Eno and his protégé, Daniel Lanois). Soft, sparkling but always just beyond the edge of discernible pattern, Budd's pieces with Eno are like keyholes to dark rooms that Budd—in his reserve—never lets you into. It's this tension—between gentleness and threat, between intimacy and uncertainty, between the thrill of a hint and the human desire to see the whole picture—that makes them seductive on first listen but so easy to play on subsequent ones. Also worth noting is a track from Budd's 1981 album The Serpent (in Quicksilver), which at 20 minutes long barely constitutes an album, but is my favorite Budd release right now—a series of miniatures less high-minded and delicate than his Eno collaborations, but earthier and more generous too, tapping into a history of jazz, Americana, and even country music that he rarely touched again.

The second half of Wind is spottier than the first—the textures less rich, the mood less sustained. "Soft pedal," an airy, meandering piano technique of Budd's own division, is supplemented by even more reverb, which can be as much of a crutch as an aid. And while I've had my swings of passionate involvement with the Cocteau Twins, Budd's collaborations with both the full band and with guitarist Robin Guthrie have never really held my attention. (Guthrie's guitar sound—somehow both chilly but indistinct—has always sounded best to me when set against the sturdy backbeat of a drum machine. Against Budd he sometimes sounds like water cut with water.)

Even Budd's less interesting pieces have a toughness to them that I find surprising and unexpected. Having held myself off from making nature metaphors in a review about low-key instrumental music until now, I'll make one: the icicle: small but sharp, seemingly transparent but impossible to see through, delicate but chilly to the touch. Wind doesn't measure up to Budd's best albums and can't, but that's not what it was meant to do. It's a primer to a composer too often cited as a footnote and too modest to correct the record. (Pitchfork)