ātamōn begins with hardware-store junk and ends somewhere close to a secular liturgy. Working with PVC pipes, water hoses, ball valves and a construction-site air compressor, Amina Hocine set out to build a foghorn organ, chasing the blunt authority of sirens and harbour signals. What emerged was stranger and more precise: an acoustic machine that sounds uncannily electronic, projecting tightly focused beams of frequency that she calls “sound crystals.” These tones, spreading like narrow lasers in space, challenge the eye’s sense of what such materials should do. There are no oscillators or laptops here, but the drones feel as controlled and surgically tuned as anything from a modular synth rack, best experienced on speakers that can let their overtones and beating patterns fully flower.

The project took conceptual shape during a residency at Skogen in Gothenburg. There, Hocine began treating composition not just as craft but as a form of self‑inquiry, rooted in years of conversations with a spiritual advisor and therapeutic work on inner archetypes. The foghorn organ was deconstructed into eight pipes distributed around the room, each aligned with a distinct psychological figure – The Safe Place, Hyperarousal, Original Face, and others. Instead of actors on a stage, pipes; instead of dialogue, air under pressure. The title ātamōn, from Old High German “to breathe,” captures this shift: the instrument as a living organism, exhaling and inhaling tensions, longings and contradictions. What unfolds is a wordless theatre in which frequencies enact the push and pull between protection and panic, withdrawal and exposure, habit and insight.

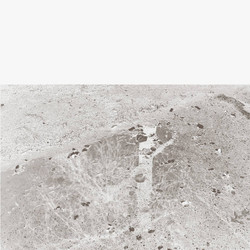

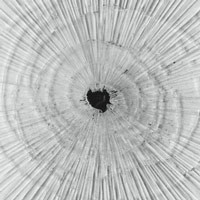

To record the work, Hocine moved the instrument into Spelhuset at Ställbergs gruva, an out‑of‑use iron mine in rural Sweden whose vast chamber once housed the giant wheels of an elevator system. The space is not a neutral box but an active collaborator, with long, complex reverberation that grabs every tone, stretches it, and folds it back onto the next. In this environment ātamōn becomes a sonic ritual – an encounter between body, metal, stone and air. Each surge of compressed breath into a pipe sets off a chain reaction: the initial “sound crystal” blooms into harmonics, ricocheting off walls and beams, producing ghost tones and low rumbles that the instrument alone cannot generate.

The work is presented in two long parts. ātamōn I focuses on the interplay of the archetypal “voices” themselves. You hear the pipes feel each other out: one steady, low anchor; another jittery, flickering at the edge of alarm; a third intermittent, like an impulse that can’t quite decide whether to speak. Each part believes it serves a purpose, even when its sonic effect is abrasive or overwhelming. Hocine’s composition gives these internal figures room not to be judged but to be heard, allowing dissonances to persist long enough that they start to make emotional sense. Gradually, without any obvious resolution, the layers settle into a rough alignment – not a tidy harmony, but a coexistence in which no single archetype dominates.

In ātamōn II, the emphasis shifts to the dialogue between instrument and space. Moving microphones through the sound field, Hocine “plays” the room as much as the pipes, activating pockets of resonance and standing waves. Small gestures – a slightly altered valve opening, a repositioned mic – trigger different responses from the mine, as if the building were answering in its own slow language. The result is drone‑based music that morphs from dense, organ‑like chords to moments of stark, piercing clarity: alarm‑like signals and interlocking polyrhythms that cut through the smear like flashes of comprehension. Elsewhere, the sound relaxes into something vast and oceanic, encouraging the listener to drift through shifting layers of resonance rather than track any linear arc.

What runs through ātamōn is a commitment to re‑enchantment: of sound, of space, of inner life. Informed by symbolic systems, “spiritual science” and psychological practice, Hocine uses her foghorn organ not to illustrate a narrative but to build what she calls a “delicate architecture of vibration” – a memory not of events, but of presence. The album doesn’t tell you what its archetypes are or what they resolve into. Instead, it opens a field in which listening itself becomes a kind of ritual attention. Pipes breathe, stone answers, frequencies clash and meld; somewhere in that exchange, the listener is invited to notice their own internal movements, the parts of self that flare up in recognition or unease. ātamōn is less an object than a space you step into – one where breath, metal and thought briefly line up, then dissolve back into the air.