An old Zen koan comes to mind; delivered through the lesser hands of seekers and compilers, beats and Deadheads, the New Age-- but surely, I imagine, of wise and noble provenance somewhere back. A flag flapping in the gale sparks an argument between two monks on the nature of things. The first declares that the flag is surely moving. The flag is still, counters the other, it is the wind that is moving. Sure enough, where an insoluble paradox appears, the wandering master is not far behind. Which is it, ask the monks, is the flag moving or is the wind moving? Neither, replies the master; mind is moving.

Fair enough. Take it, like any wisdom, with a grain of salt, but it springs to mind. Not because Tony Conrad sees still air and a flapping flag, or because Faust occupy a world of volatile weather, but just because, for a moment in Outside the Dream Syndicate, one forgets what exactly is moving and what is standing still.

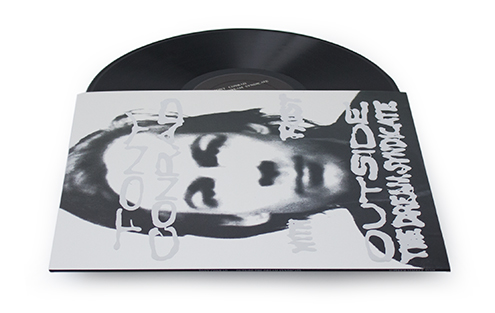

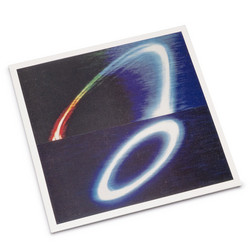

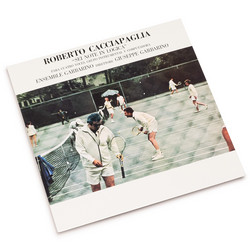

Here's what we know: in October 1972, at a hippie commune in Wümme in southwestern Hamburg, a German art-rock collective bred on the stringent drone and skag-pop of the Velvet Underground hooked up with the young composer who gave that band its name-- or rather, who handed Lou Reed the sadomasochism exposé whence the band derived its name. Tony Conrad and the members of Faust collaborated for three days on an album that would be released the following year in England and would tank immediately thereafter. The musicians did not communicate or collaborate throughout the following two decades.

Minimalism is unquestionably the wrong word; I prefer asceticism. Anyone familiar with the Zappa-like hysteria of Faust's first album or the searing kosmische of IV must imagine the sheer force of self-denial at work in implementing Conrad's vision: to have a deep base note tuned to the tonic on Conrad's violin and to have the drummer "tuned" to a rhythm that corresponded to the vibrations. Minimal in design, I suppose, but catastrophically huge in execution.

"From the Side of Man and Womankind" opens in dead motorik, the usually nimble percussive battery of bass guitarist Jean-Hervé Peron and drummer "Zappi" Diermaier, stalled out to a hollow thud-- like the heartbeat of a machine. Conrad's violin bleats mournfully, endlessly; rising, breathing, sighing, screaming, but without ceasing: relentless. Faust resisted. Peron's second bass note, inserted against Conrad's wishes, adds a spring and thrust to the proceedings. Zappi's odd cymbal crash shatters like punctuation in a prayer. Faust producer Uwe Nettelbeck dulled the serrated violence of Conrad's violin, somehow rendering slow murder into long caresses. "The Side of Man and Womankind" runs like a conveyor belt through fog: going without moving, advancing, standing still.

"From the Side of the Machine" is oddly less mechanical than its counterpart. A half-hour in length, like "Man and Womankind", the "Machine" side ruminates with muted psychedelia: serpentine bass, ceremonial percussion, the purr and roar of Rudolf Sosna's humming synthesizer, Conrad's violin passing high above like an electrical storm in the upper air. There is a predatory quality to the "Side of the Machine": an encircling peril, a certain restlessness above and behind. Mind moves, as if hunted.

The Thirtieth Anniversary Edition of Outside the Dream Syndicate adds a second disc of material. Two brief tracks-- both named with the young death of former Dream Syndicate comrade Angus Maclise in mind-- offer the remaining fragments of those three days at the abandoned schoolhouse studio at Wümme. Both the slow burning "The Pyre of Angus was in Kathmandu" and the tremulous "The Death of the Composer Was in 1962" reveal a looser agenda in the sessions. In the latter piece, Conrad abandons the impassive drone of the first disc for an almost celebratory psych-rock. The second disc is rounded out by an alternate production of "From the Side of Man and Womankind", lacking the overdubbed violin lines of the album version.

So perhaps a little Zen, perhaps a little cataclysm. After all, as Lou Reed said, "It's the beginning of the New Age." And a few decades before that, a poet ended his long flirtation with Buddhism by joining the Church of England. In his conversion poem, however, he continued to pray with eastern paradoxes. "Teach us to care and not to care," T.S. Eliot intoned, "teach us to sit still." And this album finally begins to show us how.