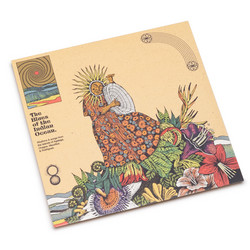

Various Artists

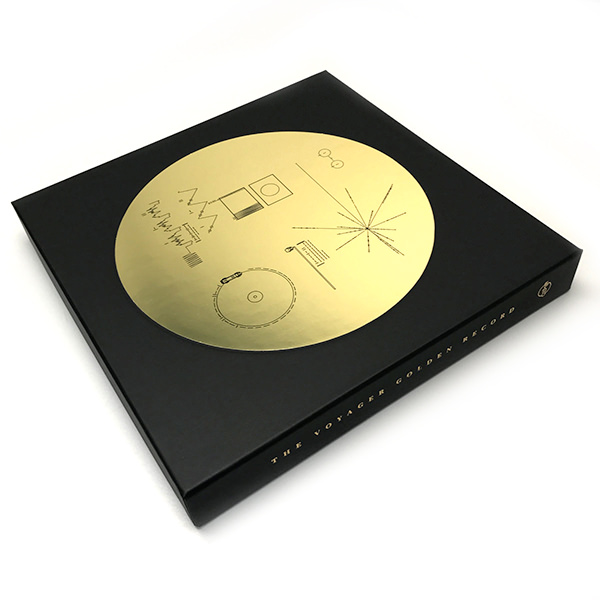

The Voyager Golden Record (3LP Box)

In 1977, NASA launched two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, on a grand tour of the solar system and into the mysteries of interstellar space. Attached to each of these probes is a beautiful golden record containing a message for any extraterrestrial intelligence that might encounter it, perhaps billions of years from now. This enchanting artifact, officially called the Voyager Interstellar Record, may be the last vestige of our civilization after we are gone forever.

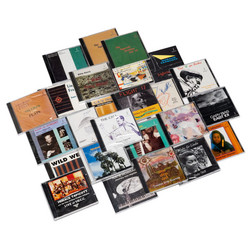

The Golden Record tells the story of our planet expressed in sounds, images, and science: Earth’s greatest music from myriad peoples and eras, from Bach and Beethoven to Blind Willie Johnson and Chuck Berry, Benin percussion to Solomon Island panpipes. Natural sounds—birds, a train, a baby’s cry, a kiss—are collaged into a lovely audio poem called “Sounds of Earth.” There are spoken greetings in dozens of human languages—and one whale language—and more than 100 images encoded in analog that depict who, and what, we are.

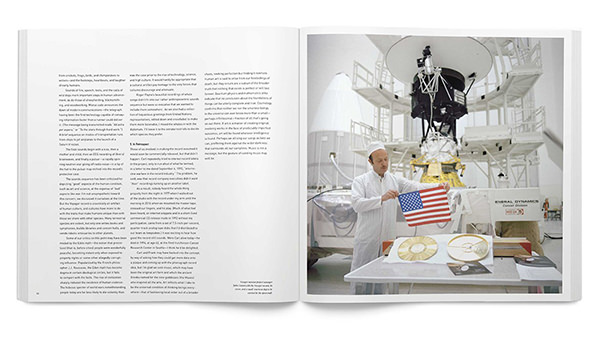

Astronomer and science educator Carl Sagan chaired the Voyager Interstellar Record Committee that created this object, which is both an inspired scientific effort and a compelling piece of conceptual art. Astronomer Frank Drake, father of the scientific Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), was the technical director, writer and novelist Ann Druyan was the creative director, science journalist and author Timothy Ferris produced the record, space artist Jon Lomberg was the designer, and artist Linda Salzman Sagan organized the greetings.

As we embarked on our own Kickstarter project to make the golden record available on vinyl for the first time, in celebration of Voyager’s 40th anniversary, we realized that we saw the original artifact through three different lenses. As an exquisitely curated music compilation, the Voyager record is an inviting port of entry to unfamiliar yet entrancing sounds from other cultures and other times. As an objet d’art and design, it represents deep insights about communication, context, and the power of media. In the realm of science, it raises fundamental questions about who we are and our place in the universe. At the intersection of those three perspectives, the Voyager record is a testament to the potential of science and art to ignite humanity’s sense of curiosity and wonder.

Voyager 1 entered interstellar space in 2012. As of this writing, it’s almost 21 billion kilometers away from Earth. Speeding along at 17 kilometers per second, it will take another 40,000 years before the spacecraft passes within 1.6 light-years of a star in the constellation Camelopardalis. The slightly slower Voyager 2 is at the outermost edge of our solar system, where the sun’s plasma wind blows against cosmic dust and gas. Soon, it too will venture into interstellar space. We may never know whether an extraterrestrial civilization ever listens to the golden record. It was a gift from humanity to the cosmos. But it is also a gift to humanity. The record embodies a sense of possibility and hope. And it’s as relevant now as it was in 1977. Perhaps even more so.

The Voyager Interstellar Record is a reminder of what we can achieve when we are at our best—and that our future really is up to all of us.

-

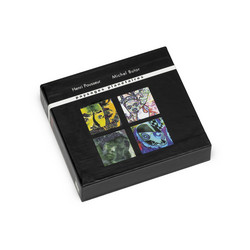

• Three translucent gold 140 gram vinyl LPs in poly-lined paper sleeves

• Three heavyweight jackets, gold ink on black

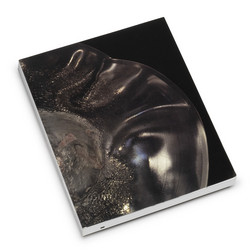

• Full-color 96-page softcover book containing all images included on the original Voyager Interstellar Record, gallery of images transmitted back from the Voyager probes, and a new essay by Timothy Ferris, producer of the original golden record

• Gold foil print of Voyager Golden Record cover diagram, archival paper, 12" x 12"

• Voyager trajectories turntable slipmat, gold ink on black felt

• Full-color plastic digital download card for all audio of the Voyager Golden Record (MP3 or FLAC formats)

• Housed in a deluxe record box with pull-ribbon, gold ink on black