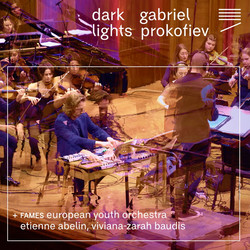

Alien Alien, Gabriel Prokofiev, Foresta

Visioni Fuggitive (LP)

* Deluxe edition of 200 copies, comes with an insert * Even Rodion has known from an early age the fascination for classical music, for scores and their secret code. And he too was a young rebel at the conservatory. Since the first meeting the two Alien Alien (Rodion and Hugosan) have embraced Sergei Prokofiev's Fugitive Visions as an inexhaustible source of inspiration towards the sublime, alienating tension of play sweetness-desire-fear. Finally they perform them together live and from the recording the diviner DJ and producer Marco Foresta paints a lunar landscape. The text below is taken from a conversation with Rodion for the Evening school / Sound bath cycle curated by Pescheria for the Teatro di Roma - at the Teatro India, on 3 December 2020.

Sergej Prokofiev was born in 1891 in the remote Ukrainian countryside where his father was an agronomist while his mother, with whom he spends a lot of time, belonged to a family of serfs. Traditionally, the children of these families were taught a variety of artistic disciplines and her mother was therefore able to learn to play the piano, passing this passion on to her son.

Little Prokofiev is passionate and his mother suggests that he follow a more authoritative teacher. So an old Russian arrives at the house, a severe conservatory teacher with a mustache, who provides him with the tools to begin analyzing the music of the great classics and understand harmony. Sergeij was from an early age a young rebel. Mom told how he didn't like playing the black keys. He played strange melodies only on the white keys. At 13 he had already composed 70 piano pieces, two operas, a symphony. And again at the age of 13, in 1904, they introduced him to Rimsky-Korsakov, the grand old man of the St. Petersburg Conservatory. That environment would like him to be different and he begins to be a kind of “alternative” guy. He was a lanky madman who composed strange songs because he liked to do things that people would talk about. It was in the moment of his compositional blow: he had to make it strange. Perhaps also because a symphony he had written at the age of 11 was previewed in St. Petersburg by a famous pianist of the time who described it as a symphony for kids, with banal, unoriginal harmony. He didn’t forget this, going even further in search of bizarre solutions.

From 1913 to 1918, when Prokofiev finishes the conservatory and composes the Visions, epochal upheavals are taking place in Russia and in the world: the revolution, a world war, the affirmation of the theory of relativity, the explosion of the artistic avant-gardes. In addition to Prokofiev, Stravinsky and Scriabin were also active in Russia; in France Debussy and Ravel, in Vienna Schönberg, Webern and Berg. There was an absolute cultural ferment as perhaps only during the Renaissance. The traditional view of music was beginning to be very narrow and stagnant. In all this lived the young rebel Prokofiev. It was essential for him to interface humanly and musically with an all-encompassing reality like that. In St. Petersburg there were musical afternoons outside the conservatory where this bizarre long-haired music of the time was played. The last printed scores arrived from Russia, Vienna and France (the phonograph was in its infancy) and Prokofiev, together with a series of crashed friends, had created a collective in which the new music of Skrijabin and Ravel was played on the piano between the others. If the scores were for orchestra, they re-arranged, rewrote and analyzed them, having extreme confidence and knowledge of the whole panorama of contemporary music. Prokofiev was totally immersed in this wave. They entrusted him with the St. Petersburg premiere of Schönberg's three pieces for piano Opera 11 which represent, with respect to what has been the harmonic and pianistic evolution of music up to that moment, a moment of total rupture. In these years Prokofiev exploded in St. Petersburg, writing an avalanche of piano pieces, concerts for piano and orchestra and working on another composition…

The new currents dismantle the concept of tonality and loosen up to disintegrate the rules that date back to Bach's times, on which Western music had been based up to that moment. The rigid hierarchical relationships between the notes are completely or partially erased, above all in the end of a piece: you can go wherever you want, modulate, then change between various keys, but the end of the piece is the moment in which, dear composer, you must absolutely tell me in which key your piece is!

If the Vienneses venture into this extreme path reaching results that are sometimes difficult to follow, however, this does not happen with Prokofiev. This is music that has a rather alienating effect, but also goes straight to the heart. Like all new music, it is received with difficulty by the older generations, but slowly it takes hold and its harmonic language can still be found today, especially in music for images, in soundtracks.

Prokovfiev takes his cue from the indications and ferments of his contemporaries and elaborates a musical language all of his own, at the same time naive, direct and very modern as we later find in the Fugitive Visions. This was for him a collection of descriptive hallucinations of what was around him. In the afternoons of St. Petersburg Prokofiev plays the works of Schönberg and from this kind of atonal music he takes this taste for suspended endings, for music that does not have to end necessarily in dominant and tonic, as it was up to then. He gets a taste for extreme tonal ambiguity: what key are we in? I can't tell. In the case of the Visions and for most of his pieces I couldn't tell you which key we are in, sometimes there are even two keys at the same time. The endings of the Visioni Fuggitive are the most absurd thing because they are extremely coherent endings but which at the same time have absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the piece and with the next one. Yes, the endings are absolutely the most interesting parts in my opinion, the most innovative of this whole cycle.

The form of the prelude is a short and very free form in terms of style and structure: the prelude can be fast, slow, polyphonic, monophonic, precisely prelude. Introduction to something that comes later. The prelude has always been a bit of an outlet for the composer: the shortest, most liberating and most ephemeral form of musical literature. It is Chopin who with his 24 preludes makes this form autonomous, no longer as an introduction to something else. I think that the Fugitive Visions from a formal point of view derive precisely from the preludes, but also from Prokofiev's boundless admiration for Schumann. The latter had already devoted a lot of work to collections of pieces, such as the "Carnaval", which are in fact portraits. This also applies to the Fugitive Visions, which are spontaneous, direct and emotional forms and which do not want to be played or fugues or anything else. Moreover, Prokofiev doesn't even give titles to the individual scores of the collection, he writes them as a set of 20 small pieces that have obsessed me for a long time. Because they're free, they don't sound like classical music, but they're not too weird either. There is always a particular balance.

They are one-minute pieces, sometimes even 30, 20 seconds long, in a completely free order. When he publishes them he says that all 20 of the Visions can be played, they can be played in the order in which they are written, but also in another; you can play one, three, five and so on. For this reason it is rather difficult to find them engraved all together.

The Fugitive Visions are composed around his 22/24 years, between 1914 and 1917.