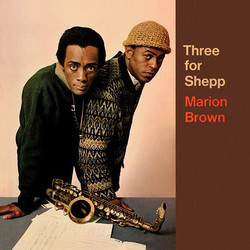

Marion Brown

Why Not? Porto Novo! Revisited

The mid-1960s were an astonishing fruitful time for creative music and there were a number of labels committed to advanced and avant-garde music. Perhaps the most doctrinaire and strict-constructionist of these was ESP-Disk, run by lawyer Bernard Stollman. Though there were to be exceptions, most of his catalogue was in highly advanced forms and in many cases represented the work of artists who had not recorded before, or only very little. One of these artists was a young man from Atlanta, Georgia, alto saxophonist Marion Brown, who'd studied law as well as music, and briefly considered becoming an attorney. The record Brown made for Stollman in 1966 wasn't his first, but it gave him an opportunity to showcase his own writing under conditions largely under his artistic control and without A&R intrusion.

Why Not? is a record that still takes the breath away more than fifty years on. The writing is astonishingly mature, for Brown was already 35 and not a youngster and for the session he assembled a group that, as he told me years later, represented exactly what he wanted for his music. Stanley Cowell's solo on the opening "La Sorella" opens up such a web of harmonic possibilities that Brown's own statement, when it comes, seems inevitable, foreshadowed as much as startling in its intensity. His interaction with Rashied Ali is as empathetic as anything the drummer did with Coltrane, and Sirone's solo marks a radical change in the music; when Brown re-enters, he seems to have had a vision, but one that he can't quite articulate, only hint at wistfully.

The opening track would be astonishing enough, were it not to be followed by the most beautiful ... we can't quite call it a ballad, of the decade. "Fortunata" has rarely been attempted by others, and is rarely adduced in discussion, but again it is made possible by Cowell's almost classical exposition of the chordal implications, which are richly chromatic to the degree almost anything seems possible. Where a lesser player would have built the material up, up and up into some kind of shouting climax, Brown maintains the same level of energy throughout. If "philosophical" implies "dull" to you, think again: this is music of the highest emotional as well as intellectual order.

On "Homecoming", Brown insists that his roots are in the past, and as much in the land and its people as for the characters in Toomer's Cane. Everyone in the group has a story to tell, a different road travelled across the lines of Brown's beautiful composition.

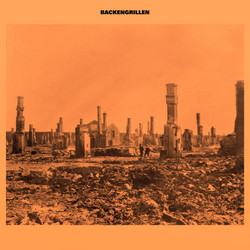

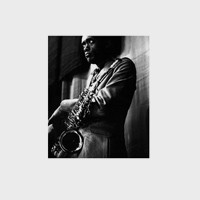

Travel is a key concept and reality in Marion Brown's life and music. He was a man never at ease with the world of jazz clubs and dances. He more than once considered giving up music, until he realised that there was a way to make the music he wanted. Brown grew up in a seaboard state and while Atlanta was a railroad town rather than a port like Savannah or Charleston, it bore a name that reminded itself constantly that there was an ocean out there and beyond it a mysterious Old World. Never a very "Southern" town in its architecture because of the influence of the north-south rail link, Atlanta had to be rebuilt after the most destructive wave of the Civil War swept through it. Brown grew up fascinated by architecture. He travelled for a time in Europe where Porto Novo (significant title!) was recorded, feeding his hunger for buildings, abstract art and an ever-widening circle of cultural associations. He told me that the post-Second World War rebuilding of Europe, which was still very much in progress when he went there in the later 1960s had affected him deeply, and particularly the presence side by side of old and new architectures; he made an explicit connection between this and his music, which was intended to be modernist and exploratory but also drew deeply on older folk traditions.

It's significant that he somewhat turned his back on America during the decade that was - and still is - supposed to represent freedom from racial, cultural, parental, political constraints, and the right to express oneself without check. He said that what impressed him about European musicians, and there are some very fine ones on Porto Novo, was their stronger sense of continuity and the need not just to tear up old codes but to work through them to something beyond. Urban Holland was devastated by the Nazi bombardment and along with some of its loveliest buildings, whole archives of music and literary manuscripts were lost. That might seem to invite a kind of radical, blank-page freedom, but what appealed to Brown about his Dutch colleagues was their desire to remake the present in the presence of the past.

At first glance the two supporting musicians on Porto Novo are as different as one could imagine. Han Bennink, who had recorded with Eric Dolphy, is often portrayed as a showman, even something of a clown, a label that fails to acknowledge Bennink's extraordinary time-sense and respect for the earliest traditions of jazz. In contrast, Maarten van Regteren Altena is perhaps better known as a serious composer than as a jazz bassist, but he, too, understood the nature of rhythm, as well as harmony, in early jazz.

At first hearing, "Similar Limits", which opens Porto Novo, might strike a listener as something by Ornette Coleman, perhaps with the David Izenzon/Charles Moffett trio, but while the stop-start melody could be Ornette's the lyrical sweetness of the alto line is very different. Bennink's deliciously clattery drums and Altena's yawing bass help complete an altogether more individual impression. Coleman drew on the past as well, from blues, church music and field hollers, but his was a more aggressive modernism. The opening of "Qbic" might prompt a similar reaction, but listen to how subtly broken up the implied harmonies are, as if Brown was thinking about Cubism as well, with its reliance on African art models. And that gorgeous alto statement at the opening of "Improvisation" brings to mind a whole host of associations, from blues right back to the music of the Gold Coast/Ghana.

In pairing these records, ezz-thetics offers a new understanding of Brown, not just as a member of the American New Thing but as an artist who thought on an Atlanticwide scale, oceanic in breadth and depth and beauty. With this reissue, and its partner Marion Brown: Capricorn Moon To Juba Lee Revisited, ezz-thetics 1102, which put the saxophonist alongside the almost forgotten Alan Shorter, ezz-thetics has restored a valuable body of work that deserves to be acknowledged not in the fringes of modern jazz, but in its topmost rank."- Brian Morton