Trevor Watts: a legendary man, an exceptional saxophonist, a forerunner of everything that is really valuable in European improvised music, turned 80 last year. As a still active and extremely creative musician (his latest productions can be found primarily in the Listen Foundation! catalog), his long creative journey took many artistic challenges. So before you reach for the music contained in this box set, here is a brief historical outline. Around the mid-1960s, after sharing their musical experience while performing honorable duties in Her Majesty's Army, three British 20-year-olds decided to intensively create music of their own, trying to familiarize themselves by listening and watching the craft of jazz idols through the prism of their boiling ideas, which were saturated with concepts of freedom, equality and communism. Fortunately, each evening London's "Little Theater Club" provided them with a small attic room. These gentlemen were named Paul Rutherford, John Stevens and Trevor Watts. Nobody remembers exactly who called this bunch of enthusiasts the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, or why. Over the next 10 years, together with Evan Parker, Kenny Wheeler, Evan Parker, Barry Guy and others, they developed their collective version of freely improvised music that eventually became a permanent of the language of the music World Wide to this day. At the same time, since 1967, Watts and his colleagues, as part of a stylistic breakaway, realized themselves artistically in the Amalgam formation, which, starting from post-Ayler free jazz, became an improvised formula that boldly used electric guitars and at times a true rock rhythm section. This chapter came to a close at the end of the 1970s. At the dawn of the next decade, Watts redirected his fascination toward music he used to call "Moiré." But now the artist will tell us about it. - Andrzej Nowak, Spontaneous Music Tribune

When I left London after 20 years to live on the South Coast of England, I realized I was leaving the whole music scene that I knew so well. The reason we as a family mainly did that was that we were living on a main road and we had two very young children. Also, houses were cheap here then, as no one wanted to live here that much at that time. So, it meant we could expand our living quarters in a very beautiful place by the sea and improve our lifestyle. This was the year 1981. That made me get much more into composition than before. I started to write music for a set of people that I knew that would eventually become the first 10-piece ensemble, Moiré Music. The name of the group was coined by my partner, Margaret, who suggested that the name seemed to fit the music I had written. She knew the paintings of, say, Brigid Riley, which visually represent that name. I understood the word “Moiré” in simple terms. It meant that two or more patterns can make a third and so on, so that is in the ear, in this case, or the eye of the beholder. What you see/hear is what you see and hear. I based the writing on interlocking patterns, and lots of them.

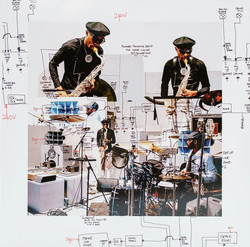

The music has often been called minimalistic. But that was never in my mind. Rhythm has always been very important, and rhythm by its nature is Moiré in a way, and can be called minimalistic. So the influences for me were more from traditional African music, right back to the roots. So then, you can invent what you want based on those roots, rather than using something else that was already derivative as the basis. In 1982 I was given a spot with Moiré Music at the Bracknell Jazz Festival and at the Roundhouse sessions in London, and both were fantastically well received. Also in 1982, I launched what I now call Trevor Watts Original Drum Orchestra, and that first version, more or less, you can hear on the CD's “Drum Energy” or “Burundi Monday.” I used Moiré Music at that point mainly for the writing and compositional side, and Original Drum Orchestra for improvisation, using a combination of an African musician, a folk musician and rock musician, and myself who started out as a jazz musician. None of this was influenced by jazz rock or anything like that; it was an attempt and belief that anyone could make interesting music together if the desire, and of course skill, was there to do it. That was the principle.

As I said before, in the 1980's I wanted to have a group that purely improvised, and then a group that was a vehicle for my compositional side. Of course, improvisation by way of solos still played a big part. Everything has a natural life, but also juxtaposed with my feeling that Moiré Music had more or less come to an end in 1990. It was then I decided to finish with the Moiré Music project and put everything into what I called Moiré Music Drum Orchestra. We also started to play compositions at that period too. Not only by myself, but by other members of the group. Colin McKenzie used to come to my home a lot during this period, and through his bass guitar playing, helped shape how the music would become, as well as some compositions from the African musicians. By the time we played the music on this set of recordings, the group was drastically changing in personnel and was heading toward the end of its life.

All the recordings we can listen to in a 5-disc box set are equally close to me. They all offer different interests within my musical career that I have been involved with, and by no means are these all of them. If we take them one by one, the closest to each other musically speaking are the two Moiré groups. This represents my involvement with African musicians, which lasted around 15 years, touring all over the world on many occasions and great collaborations with, for instance, the “Teatro Negro De Barlovento,” a group from the Caribbean region of Venezuela, or workshops at the Film Institute of India in Mumbai. My passport to the world.

An especially remarkable achievement was a concert of Moiré Music Drum Orchestra posted on Disc 3 (and the first track on Disc 4). This performance was extraordinary in many ways as we headed on a 10-hour drive from Hamburg down to Lugano in the Italian part of Switzerland. It was the even more remarkable cartoonist friend of mine, Martin Honeysett (of Private Eye magazine, etc.), who drove all the way, almost nonstop. Martin loved driving and he loved the band and he was a very good driver indeed. In more “hippie” times he drove the Magic Bus, I think it was called, to Turkey and other places from the U.K., so he was a seasoned driver. He got us there by the designated time of 18.00 hours, when the producer and others were waiting with, I’m guessing, slightly frayed nerves. They helped us in with our gear. It was a live audience, you see, and so we did a quick sound check, took off our coats etc., and proceeded to play this concert. Such is life in the fast lane. The audience’s appreciation was felt all the way through. Magic moments. Martin’s cartoon of the band can be seen somewhere else in this boxed set as a sample of his work. I also dedicate this concert to him and I know everyone would have agreed.

The collaboration with Gibran Cervantes in Mexico came about because when he was about to make his first recording, someone in Mexico had heard me play with the Moiré Music Drum Orchestra and had said that I was the one who could do the job. Gibran started out with about 10 musicians, and by the end the recording just featured himself, Brazilian percussionist Cyro Baptista and myself. Gibran and I became very close and I started to go over to Mexico very often for concerts around the country. I then introduced Gibran to Jamie Harris and we played as a trio. So you can see how the Moiré thing was connected, in life terms, to the Urukungolo trio.

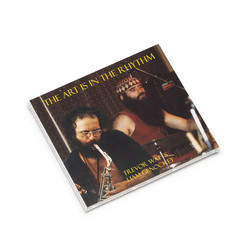

Then there's the duo work with Jamie Harris. When I met Jamie he came to a workshop of mine. He sang and played guitar, but only did vocals at the workshop. I said I didn't really have anything for vocals, but gave him a Tarabuka drum and showed him a rhythm, which he immediately picked up and played. So I said to him that he was a drummer. He really did have that very natural drumming thing with his hands and energy, and we used to get together three times a week as he lives here in the same town, and for quite a few years we played as a duo and developed the music. It all lasted around 2000 to 2005. It can safely be said that I mentored Jamie during this period. I even got a Tarabuka myself and played the hand drum regularly to show how the rhythms worked with the melodies. I was always tapping anyway, all through my life, and still do. So we went out a lot and played our hard won music, sometimes with the two drums, some of the rhythms we had worked on and then the sax. You can hear at least one of the tunes featuring us both. It was great that eventually we could play two nights in Sao Paulo at the Jazz Festival to a full audience on both nights. The second night they were joining in with some of the vocals. The evidence is on the “Live in Sao Paulo, Brasil” CD.

Just over a year ago, in 2019, Jamie suggested we get together again after he’d initially been asked to play with me by my other major duo partner of over 40 years, Veryan Weston, who very kindly and generously organized my 80th Jubilee celebration gig in London. And so we have been rehearsing, this time, once a week when we can, and no drumming from me. We are building our musical pad up again and beginning to play more concerts. Jamie lives near me, so that makes life easy in terms of developing something I think is worthwhile. It’s not about gigs for me, it’s about the music! Don’t get me wrong -- I love doing gigs.

The final CD in this set is with Mark Hewins. Well, Mark Hewins replaced Keith Rowe for a very short while in Amalgam in 1980. I thought he was the only player I knew at that time that could do so. Mark used to go and play with Keith at his house in London as they both lived in Streatham at the time. But by the time I reconnected with Mark he was living on the South Coast and I used to get a train and we'd do some playing and recording. And these are the results of our collaboration. Mark and the way he plays gave me a very different palate to play with. It gave me the freedom to play in a more conventional way and experimental way, and at the same time, whichever way the muse takes us, and whatever came to mind. For me it’s always a collective thing, and so I will respond to any perceived changes or change of direction, however slight. I am not that type of player that ignores. I cannot help responding in whatever way seems appropriate to me at the time. Mark is a generous spirit, and that is a strong part of the glue.

You can see by reading this how everything for me is done in as "natural" a way as possible. Like the music itself, it doesn't always best serve me because I know promoters need to have a good idea of what they are getting. I am OK with that, as my prime concern is the development of the music in whatever way it comes up and also with others. It's called commitment. - Trevor Watts, May 2020 in the year of the coronavirus pandemic