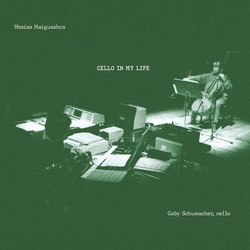

Gavin Bryars

After The Requiem (LP)

Original 1991 LP edition Stepping into the territory of Gavin Bryars is like coming home, so familiar are the morphemes with which he composes his musical language. One of the most significant recordings in the Bryars catalogue, this disc offers a fine condensation of his spirited and nostalgic sensibilities.

After the Requiem dates from 1990 and follows his Cadman Requiem of the previous year. After completing the latter, which was written for the Hilliard Ensemble in memory of Bryars’s friend Bill Cadman, Manfred Eicher suggested that Bryars spin an instrumental postlude from the requiem’s latent fibers, thus giving us the title piece of this brooding and gorgeous album. Scored for two violas, cello, and electric guitar, After the Requiem offers a distinct take on the state of mourning it so affectionately recreates. Like the gravelly strings that open the piece, the mood is raw and unbounded. Frisell’s guitar sears the darkness like the northern lights with a slow and lustrous fire, bleeding spectral life force into the evening sky. The strings gather momentum, as if to coax the guitar toward the horizon, chasing the memory of an afternoon that can no longer be recovered. Frisell plays as if he were bowing the guitar, drawing out an amplified sustenance that nourishes the vocal hunger of his accompaniment. Where the strings seem to mimic voices, the guitar mimics the strings, ad infinitum. The piece slows about midway through, burrowing even deeper into contemplative soil, at which point Frisell wrenches out some grinding low tones from the lower register of his axe. What would be but one voice lost in a power chord more forcefully played rings here with the humility of supplication. Before long the guitar lets out more substantial tones and shifts to an aerial shot of the same landscape. The earth recedes, leading into the most beautiful moment of the piece, during which the guitar drops from a soaring high note. One can hear, indeed almost taste, the meticulous care that went into this performance. The music fades, as if sending off a spirit to a realm where life continues of its own accord. The continuity between instruments here is such that there are almost no audible gaps between them. And while all the musicians play with consummate grace, Frisell is nothing short of astonishing. Despite the polished feel of the piece it was the result, as Bryars makes clear in his recording diary, of much refinement and experimentation on Frisell’s part, working closely with the composer to achieve the ideal effect.

The Old Tower of Löbenicht. This piece, composed in 1986, is the early version of an instrumental interlude for a yet-to-be-realized opera adapted from Thomas DeQuincey’s The Last Days of Immanuel Kant. Says Bryars, “It occurs at a point in the opera where Kant is disturbed at the way in which growing poplar trees have obscured the view of a distant tower which ‘he could not be said properly to see…but (which) rested upon his eye as distant music on the ear—obscurely, or but half revealed to the consciousness.’” The music is meant to evoke Kant’s divided response to the tower’s presence and obfuscation, hence the nocturnal bass clarinet and ominous bells that dominate the first half. The music moves like a barge through ice flows. Its signals ring across the waters to the mainland, traversing coastline, steppes, mountainous terrain, barren fields, contaminated pools. A solemn piano appears with a rhythmic and minimal motif, rocking between two-part harmonies, as Balanescu solos beautifully on violin, at times doubled by Roger Heaton on bass clarinet. This progression is landmarked by a plucked bass and vibraphone. Bryars weaves a few audible strands of light into the otherwise requisite darkness, where constellations are but a memory lost to annals of history. The music very much resembles the trajectory of Glorious Hill, another Bryars masterpiece. The sheer clarity of Balanescu’s tone, at once thin and rich with melodic substance, is the binding thread. As the piece ends, a marimba flutters like butterfly wings in and out of our sonic purview, leaving behind a litany of bells while a bass clarinet scrapes the bottom of its available registers.

Alaric I or II (1989) is scored for two soprano saxophones, one alto, and one baritone. “The title,” Bryars tells us, “comes from the name of the mountain, Mount Alaric, in South West France, opposite the Chateau where I spent the summer [composing this piece]. No-one seemed to know which of the two ‘King Alarics’ the name referred to.” Alaric I or II is an exercise in virtuosity, requiring of the players a variety of techniques, including long bouts of circular breathing and controlled multiphonics. As with the rest of the album, this piece builds slowly yet with purpose. After a series of languid dissonant clusters the alto sax sketches a theme in its haunting surroundings. Suddenly, the two soprano saxes launch into a rhythmic arpeggio, lending a Philip Glassian flavor to the palette. Soon this thins out in a more contemplative air, pausing on a resolved chord, further darkened and reformed into a new beginning. Another rhythmic section begins as the baritone sax raises its throaty call. From this point a steady energy is maintained by at least one instrument as the others play over or around it: one lead is immediately switched off for another, typically between alto and soprano. An evocative fluttering technique signals a close as the quartet subsides into quiet agreement, hermetically sealed and indistinguishable from the rest of the rocky cove. The musicianship here is superb, the saxophonic sound rendered with precision. At times this piece shares an affinity with the brief saxophone quartet in Michael Nyman’s soundtrack for The Piano and would be equally suited for some incidental purpose. Although this is a fairly minimal piece, it evokes a range of atmospheres and images. Its energy moves in peaks and valleys, opening the earth’s bindings just a little further to smell its ink-blotted pages. It’s like a captain’s log floating unseen in the wake of shipwreck, plowing the waves for days before the water turns it into invisible molecules.

Allegrasco (1983) is an “operatic paraphrase” of Bryars’s first opera Medea. It is another larger ensemble piece that opens humbly with piano and clarinet. Brooding strings wrap their arms around the central melody. A bell intones; the strings grow louder; the clarinet snakes its way around like a loose scarf caught in a strong but silent wind. A playful passage ensues, a dance in a silent film. The guitar grows into a more supportive voice, dropping remnants of the album’s title piece into this limpid pool. Allegrasco is a series of finely wrought vignettes, each turning like a musical waterwheel. The music is never still, as if at the whim of an unseen narrative force. We graze the shoreline with each musical gesture, sometimes sinking, sometimes floating.

Bryars’s music practically begs for imagery, if only the listener’s own. It is corroded, antique, and accrues value with age. One hears it anew every time, for it holds a world of possibility.