We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

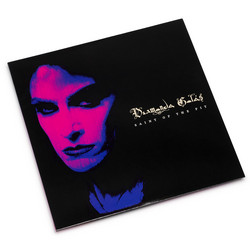

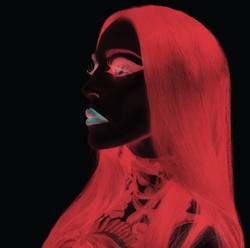

Diamanda Galas

Broken Gargoyles

Employing a vast array of advanced vocal and instrumental techniques, Broken Gargoyles is arguably Diamanda Galás' most intellectually, sonically and viscerally formidable work to date. The album finds the visionary artist deftly probing the weaving, warping transformation on the nervous systems of her post-traumatic soldiers and dying diseased. The album's first part, "Mutilatus," contains the Georg Heym poems "Das Fieberspital" and "Die Dämonen der Stadt," and concerns the suffering of the soldier in the trenches and during innumerable operations in the hospital. Composed in 2020 during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the first incarnation of Broken Gargoyles was played as a sound installation at the Kapellen Leprosarium (Leper's Sanctuary) in Hanover, Germany.

This sanctuary was built around 1250 and served as a quarantine for those who suffered from the plague and leprosy in the Middle Ages. The work was finalized in 2020 in collaboration with the artist and sound designer Daniel Neumann.

"Broken Gargoyles makes most contemporary black metal, edgelord power electronics or exploring-feminity-through-witchcraft-wailers (there are a lot of Fisher Price Diamandas around at the moment) sound like they’re auditioning for a role in a local production of an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical.“ The Quietus

Thirteen seconds into Broken Gargoyles, Diamanda Galás begins to sing. It is a note that hovers over a rough background drone, a single frequency frayed at the edges like a raven with feathers missing from its wing. It is joined by other vocal sounds, all similarly fractured, a choir of noises that sit just the right (or wrong, depending on your constitution) side of comfort. Further drones emerge. There is a crash. Two and a bit minutes later, a metallic ping. The ceremony begins.

There is simply no music like Diamanda Galás’. Nothing that I have heard has such a specific capacity to move.. Encountering her infrequent live sets, I have entered a trance-like state with no chemical or alcoholic assistance, have felt my body start to shake involuntary, have burst into tears. When she performed the songs of Jacques Brel at the Barbican some years ago, she stripped away the jolly bonhomie and exposed their core – the grotesque sexuality, the broken drunks, the unedited humanity.

Even listening to twelfth album Broken Gargoyles for the first time, on headphones in the quiet of a library, placed me in a curious, heightened emotional state. A Japanese martial arts expert once told Galás that her voice deploys “kill energy”. People in electronic music spend thousands of pounds on modular synths, music editing software, monochrome tattoos and clothes by Rick Owens to try and make music that comes across as replete in coruscating dread as this. All fail. Some even go to the trouble of acquiring or channelling PhDs in cultural theory to enable them to write nonsensical press releases to justify their emotionless mithering. This is a practice (it definitely is a practice) a learned friend calls “CV inflation”. Even these are doomed.

For what they neglect, and what Diamanda Galás has in every single note of the music she produces, is soul. No matter how vast the range she is able to occupy with her sui generis vocal ability, no matter how, seven and a bit minutes into ‘Mutiliatus’, she is able to sound like infernal beings pouring out of a manhole cover to the third circle of hell, there is always a beautiful humanity to her music. She understands, as so few do, that to plunge the depths of human emotion is also to see the heights, to reach the transcendent, to hold in one moment death and the bloody energy of our bodies.

This is of course frequently misunderstood. When I first saw Galás play live at the Southbank Centre, someone I was with refused to believe that all of the sound came from an unmanipulated human voice alone. Onstage, she raised her eyebrow and commented that a journalist from the Wire magazine had called her the ‘Goth Shirley Bassey’. “They are wrong,” Galás said, “Shirley Bassey is a goth”. When I interviewed her, around the same time, she laughed as she said “Diva now just means any cunt with an attitude who decides to do anything”.

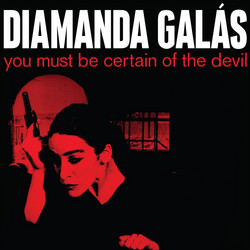

I think it’s this essential and sublime humanity that sits within her voice that allows Galás to explore subject matter that would be beyond the grasp of most artists, for whom to explore them might appear gauche or in poor taste. In the 1980s, Galás released The Divine Punishment, Saint of the Pit and You Must Be Certain of the Devil, the so-called Masque of the Red Death trilogy of albums that turned the shaming language of Leviticus into a weapon of rage to turn against the judgement of the AIDS crisis which had claimed the life of her own brother. She was also arrested for taking part in ACT-UP protests. Other subjects of her work have been the Armenian genocide, schitzophrenia and the poetry of exile. On Broken Gargoyles, Galás vocalises the words of German poet Georg Heym, who in the early 20th century wrote verses about the suffering of soldiers in the trenches of the First World War. The album’s title is also inspired by the 1914 to 1918 conflict, referencing the photographs Ernst Friedrich took of the faces of soldiers brutalised by shrapnel and bullets.

With that in mind, I look up this page and feel that my lines about ravens and “infernal beings” feel trite. All manner of gothic superlatives could be deployed in reviewing this astonishing record, but to do so not only belittles the music, but also feels like a slight take on Galás’ embodiment – or perhaps disembodiment – of the trauma of a conflict that still not only spiritually haunts our lives a century later, but in geopolitical turmoil is very much present. Suffice to say that this record is constructed around piano, violin, guitar, subterranean electronics and, above all, Galás’ astonishing voice. The sounds she is able to create, the frequencies that she does not merely visit but inhabits, make for an astonishing work of war art, an incantation for the psychologically traumatised and physically brutalised.

Broken Gargoyles makes most contemporary black metal, edgelord power electronics or exploring-feminity-through-witchcraft-wailers (there are a lot of Fisher Price Diamandas around at the moment) sound like they’re auditioning for a role in a local production of an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical. Diamanda Galás has produced not only one of her finest works, but a record that is equal and arguably surpasses other records that have the capacity to swallow you whole and spit you out that have been released in the past decade or so – Sunn O)))’s Monoliths & Dimensions, Scott Walker’s Bish Bosch, for instance. No other new record you’ll hear in 2022 so beautifully explores the limits of what the human voice is able to do, and the stories it is able to give life to while doing so. A masterpiece.

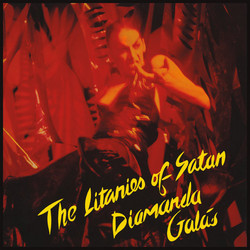

Despite Diamanda Galás’ reputation as an artist and performer with a baroque, even Grand Guignol, vision, it often feels like her real talent is not architectural or cumulative but abrasive. It scours and scrapes away – not always comfortably – layers of artifice to reveal the living emotion that leads to the creation of art in the first place. And although her image is often otherworldly, the more fundamental the human dimension to her work, the more powerful it is. As with the Masque of the Red Death trilogy that was born during the media hysteria surrounding the AIDS epidemic of the ‘80s, Broken Gargoyles took shape during the bleakest days of the Covid-19 pandemic, though elements of it were developed almost a decade earlier. The work presented here was initially part of a sound installation, appropriately developed for the Kapellen Leprosarium (Leper’s Sanctuary) in Hannover, Germany and was partly inspired by the anguished and doomladen poetry of the German Expressionist writer Georg Heym, concerned with death, sickness and war. Many of his words are incorporated into Broken Gargoyles, a pair of long compositions which are more along the lines of Galás’s The Litanies of Satan or The Divine Punishment than the relatively straightforward and more or less accessible collection-of-songs approach of albums like The Singer or The Sporting Life.

Broken Gargoyles’ two long pieces, “Mutilatus” and “Abiectio” are similar in their loose structure and only semi-musical form – they are often as much noise as music, though rarely in a one-dimensional wall of sound kind of way. “Mutilatus” is around 24 minutes long and opens with an ominous gong-like reverberation, followed by the dramatic entry of the first of Galás’ many extraordinary voices, at first accompanied by unidentifiable droning electronic sounds, but gradually multiplied into a kind of fanfare of inextricably linked voices and noise. When this dies away, Diamanda appears again, in her dramatic narrator role, intoning Heym’s poetry in her most intense and demonic tones. An understanding of German certainly helps to know what’s going on, but even without that, the themes of sickness and delirium are translated convincingly into sound, not only via Galás’ voices and piano, but through an immersive atmosphere composed of electronic noise, insect sounds, atmospherics and sparse instrumentation.

In its last longish passage, “Mutilatus” descends into familiar territory for fans of the artist’s longer works; darkly reverberating piano notes, accompanying various wails, screeches, screams and manic laughter. When the voices finally die, the piece crawls to its close with just the ominous rumbling of the funereal piano. Harsh, dissonant, but somehow very human, “Mutilatus” is as deeply unsettling and yet as starkly, viscerally beautiful as anything in Galás’ discography. It certainly won’t convert doubters, but there is nothing else in music quite like her work.

The 17-minute “Abiectio” is, in essence, more of the same, but with a more stately, baleful and even more disturbing quality. More ominous rumbling, more harsh, nails-on-a-blackboard screeches and shards of dissonant sound, this time joined by skin-crawlingly beautiful and edgy violin, so unearthly on the high notes that it sounds like a bowed saw. Over this deeply disquieting backdrop, Diamanda intones verses from Heym’s apocalyptic and delirious poetry. Again, the range of her voice is staggering, from soft and harsh whispers through to parched, inhuman howls, interpreting and acting rather than simply reciting the words. Part of Heym’s poem The Fever Hospital relates to a priest giving the last rites to a patient dying of yellow fever; this becomes one of “Abiectio”’s most chillingly intense passages, Galás’ harsh narrating voice preaching to an audience of semi-human, animal sounds. It’s not pretty, but it’s not supposed to be; instead it addresses the messy, organic nature of the human condition. The vision in her work often seems to be of a dark, hideous, distorted world, but it’s not an unrecognizable one. It is presented without pity but not without empathy. The voices of the sick and dying are terrible, but those who attend them are hardly less anguished and in the end, all face the same fate.

After listening to Diamanda Galás, most music feels sentimental, trivial even – which is something of a relief, but without her stark and unvarnished truths the world would be an immeasurably poorer place. Lots of music makes the listener feel something, but how many artists can you think of who enable you to simply feel more sharply and clearly than you did before listening to their work?

A noisy soprano sfogato of the highest order, a frightening political agitator in defense of HIV/AIDS victims, the mentally ill, and those who live unjustly, Diamanda Galás has no equal when it comes to haunting, long-form vocal poems and uncompromising performance art. I can recall every heartbeat, howl, and scream of her 1990 Plague Mass at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, the product of a woman gut shot by the angel of death who claimed so many lives in accordance with the government’s ignorance of AIDS care. Think the soundtrack to every Dario Argento Italian giallo film run through with a manic Maria Callas, The Birthday Party, and William S. Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night and that is but the tip of the iceberg in trying to describe what Galás does. As a pillar of the avant-garde, still, in 2022, Galás has neither mellowed or pulled back when it comes to rage on the two extended tracks that fill Broken Gargoyles.

Devils with necks like giraffes, newborns with no head, great demons swelling to monstrous heights, and earthquakes that set the planet’s fires alight (images wheezed and barked by Galás in accordance with German poet Georg Heym’s texts from “Das Fieberspital” and “Die Dämonen der Stadt”) line the minimalist, grumbling, low-end piano-laden score and its grandly arching horrorcore melodies. While the album’s first long, repetitive track “Mutilatus” peers into a soldier’s suffering until Galás’ cackle-howl reaches a fever pitch, Broken Gargoyles’ second half, “Abiectio,” starts with a thunderous mix of piano, sound effects, and synth squeals and allows the vocalist a foothold on every step of Hell’s seven rings. Or is that Earth that she’s lamenting? Brutal music not for the faint of heart or those with little attention span. Diamanda Galás is worth every moment of your time.

Diamanda Galás composes violently compassionate music about suffering. Her late-1980s Masque of the Red Death Trilogy focuses on AIDS, which killed her brother, Philip-Dimitri, in 1986, while other projects delve into the oppressive Greek Junta and the Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Genocides. The 67-year-old goth icon performs less harrowing stuff, too—a hard-grooving 1994 collaboration with Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones, a bevy of brilliant takes on blues standards. Yet at her best, Galás sharpens her cutting sense of empathy, slices open difficult subject matter, and approaches it from inside: Her 1991 dirge for HIV’s most deadly era, Plague Mass, might be the heaviest live record ever made. Ultimately, Galás’ haunted ritual, like all of her releases, is a ceremony of tenderness.

A master of the early 19th century style of bel canto singing, Galás uses her operatic genius to explore tropes uncommon in experimental composition—especially the breakdown of tortured, diseased bodies. Shaped from spectral piano and electronics, her soundscapes batter, unsettle, rouse us. Her virtuosic voice, inspired by avant-garde saxophonists Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman, spans an untold number of octaves. She screeches, wails, bleats, and slips between characters, usually vengeful, demonic figures skulking around like a bad conscience. Both performance artist and diva, Galás has a potent theatrical sense and a persona at once progressive and full of fire and brimstone. Echoing obsolete medical drawings that illustrate sickness as floating miasma or bodily humors to be drained, she rebukes ignorant societies while harnessing their wild imaginations.

Her latest record, Broken Gargoyles, highlights the chronic nature of our callousness toward the ill and injured. Inspired by the mistreatment of wounded World War I infantrymen, Galás unearths devastating source texts from a slightly earlier era: the verse of Georg Heym (1887-1912), son of an assistant in a yellow-fever clinic and an enfant terrible of German expressionist poetry. Before his death at 24, Heym wrote unflinchingly about sick patients, maimed soldiers, and other doomed souls he might have been exposed to through his father’s work. Setting four of Heym’s poems to pulsing, droning accompaniment, Galás traces a throughline of ostracized invalids across the past century-plus of public health catastrophes. Appropriately, she premiered some of this material at a medieval German leper sanctuary and began cobbling the album together during COVID lockdown. Broken Gargoyles targets governments’ botched coronavirus responses—implicitly, it sets sights on their homophobic sluggishness to protect gay men from monkeypox, too.

The album may not shock the singer’s die-hard fans, but Broken Gargoyles is a moving, painful listen and an ideal access point for the uninitiated. Split into two tracks, each of which hovers around 20 minutes, the record occupies recognizable terrain Galás charted out on her recently reissued early career peaks, 1982’s The Litanies of Satan and 1984’s Diamanda Galás. We’ve even heard facets of this material before: In 2020, Galás released De-formation: Piano Variations, an instrumental setting for one of Heym’s poems and a collaboration with sound designer Daniel Neumann, who returns on Broken Gargoyles.

The duo’s overhaul from solo piano to full arrangement, though, is thorough. Over the skeleton of De-Formation’s chords, the opening “Mutilatus” hangs ominous synths, eerie, wordless arias, and renditions of two poems. The composition is lush and undulating, full of voices that bedevil the edges of the audio field. There’s a palpable tension between sustained keys and Galás’ precisely articulated, staccato recitations. And while her piano is largely dissonant, when she allows herself a few snatches of somber, left-handed melody, the mood turns immediately from agonized to elegiac.

Throughout, Galás draws a singular timbre from Heym’s guttural German, approaching the language itself as an instrument. Still acrobatic and versatile, her voice sounds occasionally treated, bubbling from beneath a pool’s surface. Galás’ varied intonations circle each other, crying out from mutual isolation like ailing bodies on a long, crowded ward. Thin whimpers emanate from somewhere far off; a gurgle of filtered noise fills out the low end; repetitive chimes mock us with memories of human comforts, like a food cart wheeling down a hospital hallway. On the second song, “Abiectio,” Galás’ voice warbles between consonance and caterwaul, as strings swell from melancholic tunefulness into abject anxiety. Over muffled moans, Galás’ readings grow increasingly desperate: Somehow, the track manages to be even more mortifying than its predecessor, a coda from beyond the grave.

While she’ll always be admired for her remarkable singing ability, Broken Gargoyles draws our attention to Galás’ conceptual, confrontational heft—a quality we haven’t heard from her on record since 2003’s double-disc Defixiones: Will and Testament. Her mixture of literary intelligence and three-dimensional sound design feels particularly relevant today, a direct predecessor to the talky strain of noise music that links Lucy Liyou, Lingua Ignota, even claire rousay and more eaze. Yet Broken Gargoyles pushes this side of Galás’ practice to such an extreme that she still seems a world apart from other musicians, while leaving us unable to ignore the urgency of her themes. There’s a good reason that the voices on Broken Gargoyles feel so maddeningly real: Their hurt might be bygone, but sinews of experience tie it to the present. Galás shows us humankind as both culprit and victim, a self-destructive pawn that each year grows guiltier, sadder, and more overwhelmed by the weight of bottomless trauma.

Related products

More by Diamanda Galas

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm is a trademark of Nube S.r.l.