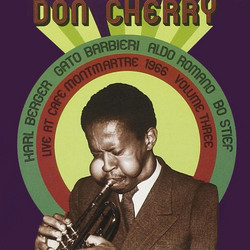

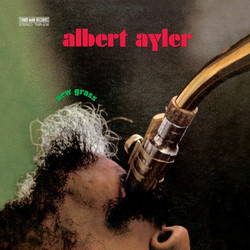

Albert Ayler, Don Cherry

European Recordings Autumn 1964 - Revisited (2 CD)

"Albert Ayler With Don Cherry European Recordings Autumn 1964 Revisited” in this context will inevitably make some people think of Revenant, the label that in 2004 issued a nine-CD box of Albert Ayler materials, almost all of them rare and unissued. The release prompted some revisionist thinking about Ayler, who has remained a controversial figure in modern jazz, hailed as a genius, dismissed as a hoax or a man in the grip of an autism, an avant-gardist who suddenly decided to be a populist instead...

The procession of different Aylers moves on. In a previous issue of the present material on hatOlogy, my colleague Andy Hamilton showed how recent thinking had moved away from or at least questioned the validity of the “genius” label. It’s a term we associate with virtuosity, which is often a surface phenomenon connected to technique rather than depth or clarity of vision, which can often be expressed in very simple forms. I wouldn’t for a moment dream of taking on Andy, who is after all a professional philosopher, in any discussion of these matters, but there is another – older, simpler – definition of genius that applies here.

When we speak of the “genius of place” we mean the distinctive, hard-to-pin-down character of a location, the impression that returns to us the moment we stop off the plane or the ferry, the combination of subliminal and sensible things that makes us think... here.

And it is the same with Albert. There is never any question as to who is playing, whether the material is a keening original theme, perhaps based, as some believe, on Scandinavian folk melodies, or a piece of rocking r’n’b, as in his final recordings. Ayler is never more or less than himself. Some might argue that this is consistent with a person on the autistic spectrum. It is known that Albert and his brother Don both had mental health issues, and Albert was known for eccentric behaviour.

I speak with relative confidence about this, having raised an autistic daughter. Her art is neither good nor bad. It might be dismissed or pigeonholed as “outsider art”, but it is utterly distinctive and could not be mistaken for anyone else’s work. Albert Ayler’s music has that character. One can argue endlessly about its origins in the projects of Cleveland, in gospel and the r’n’b that he learned around Little Walter, in the music of John Coltrane, in European music: the fact is that it remains entirely sui generis. It’s strange to note – and this was only confirmed when the Revenant box came out – that of all the great modernists Albert actually came closer to Cecil Taylor than to Coltrane or Ornette Coleman or Thelonious Monk. Taylor is “another monolith of modern jazz, seemingly unapproachable (and, like Miles Davis, particularly choosy when it came to saxophone players); and yet Taylor allowed the twenty-six year old Ayler to jam (unpaid) with his band. The music that they made is now known to us and was revelatory.

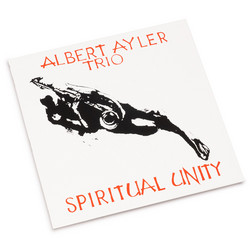

Taylor’s dense “atonality” (which is nothing of the kind) and Ayler’s “primitive” cries seemed to meet and communicate. A year later, Ayler reached his brief apotheosis with some of the most important recordings in the jazz canon. With Prophecy (ezz-thetics 1104), Spiritual Unity, New York Eye And Ear Control and the music you are holding now, he reached a pinnacle, not of experiment (which suggests something willed and intellectual), nor quite of self-expression (if that is taken to mean the unfettered paint-splashing of a child) but of self-in-music.

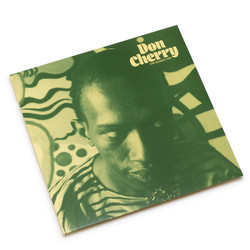

That is what we hear in these remarkable recordings. The only other figure of the time who might be thought remotely comparable is trumpeter Don Cherry. There is a chemistry that joins such people together. (Once, in a crowded room, on the induction day of a school predominantly for deaf children, my daughter and another little girls sought each other out and played in parallel, unspeaking, for an hour, apparently unaware of one another.)

Don Cherry told me once, in Poland, that working with Albert had been wonderful because “he didn’t know you were there”. It sounds an odd thing to say.

We cherish the notion of jazz musicians as listeners, as having antennae attuned to every sound in the room, responsive to the cues of bass or drums or the piano chords, or the last phrase of the preceding soloist. We are disturbed by the thought that two musicians might simply play in parallel. Albert and Don were two children set adrift in an unhearing world. They found one another and in these remarkable performances, made in a radio studio and a famous club, they simply allowed their selves to be enacted in music. What we hear is that sense of hereness. Whether this is “genius” or some kind of outsider art is hardly the issue. Few individuals, of whatever intellectual or technical rank, ever acquire the confidence or simple lack of doubt to be themselves, in the moment.

Even “great” musicians, writers, painters, hide behind technique and an awareness of the history of their art-form. Albert and Don (and how touching that Cherry echoed his brother’s name and instrument) don’t fit easily into the progressive or (r)evolutionary models of jazz history. However you draw the lines, they seem to be outliers. That, of course, was their genius, and it suffuses everything you will hear on this disc. - Brian Morton