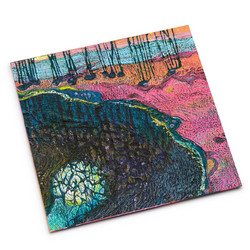

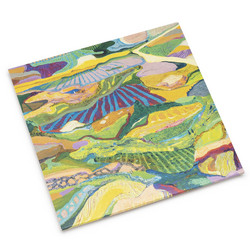

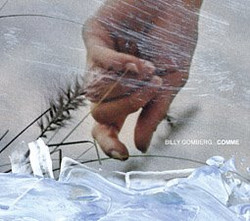

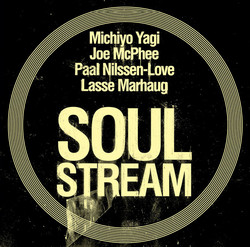

Extinguishment documents the chamber dialogue between Billy Gomberg (bass guitar, electronics, recordings) and Anne Guthrie (French horn, electronics, recordings), working as Fraufraulein for Another Timbre. Recorded over several months in 2014, the album pursues a shared language of improvisation - each piece constructed from discrete performances, then woven with a common thread of minimalism, private lyricism, and environmental observation.Field recordings, manipulated live, are inseparable from the instrumental lines: distant traffic, birds, and echoes bleed into slow-motion layers of bowed strings, low guitar, and horn, blurring boundaries between performance and ambience.

The music privileges environment and acoustic space above overt melody or pulse. Longstretches hover in a world of decaying harmonics, granular noise, and unexpected interruptions. “Convention of Moss,” the opening suite, invites the listener into a shifting landscape where percussion, bass, and horn imprint themselves as fleeting shadows - moments are precise but never foregrounded, each gesture dissolving into the next. Detailed electronics shimmer just behind the acoustic sound, while the duo’s extended techniques yield a palette of gentle disturbances, radiating calm and tension in equal measure.

Fraufraulein’s chamber method for Extinguishment is as much about shared listening and collaborative discovery as it is about performance. Each track is an unpredictable encounter, richin tactile nuance and colored by near-silence and rare, melodic fragments. The album offers a quietly radical approach to duo improvisation, where beauty hides inside blurred edges and meaning emerges from attentive, open engagement with both place and sound.