Alan Licht's minimal Top Ten

Alan Licht's revelatory lists of rare and obscure minimalism releases.

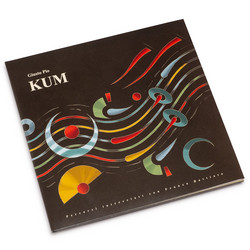

See allGiusto PioFeaturing: Franco Battiato

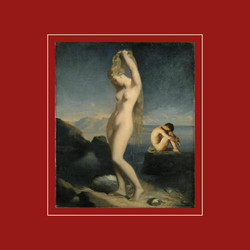

Motore Immobile (LP, coloured)

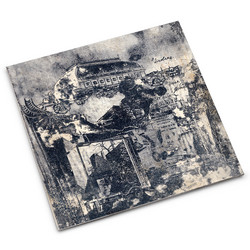

** 180 gr. Red Vinyl. Digitally remastered from the original master tapes ** One of the most striking documents of Italy’s Minimalist movement, Giusto Pio’s Motore Immobile is a masterwork with few equivalents. Produced by Franco Battiato, at the outset of a long and fruitful period of collaboration between the two composers, and issued by the legendary Cramps imprint in 1979, its triumphs were met by silence, before falling from view.

Emerging on vinyl for the first time since it’s original pressing, Motore Immobile now sits within a reappraisal of a large neglected body of efforts made by the Italian avant-garde during the second half of the 1970’s and early 80’s. It is singular, but not alone. It resonates within a collective world of shimmering sound, one familiar to fans of Battiato, Lino Capra Vaccina, Luciano Cilio, Roberto Cacciapaglia, Francesco Messina and Raul Lovisoni. An exercise in elegant restraint - note and resonance held to the most implicit need. Where everything between root and embellishment has been stripped away. A sublime organ drone, against interventions of deceptively simple structural complexity - executed by Piano, Violin, and Voice. A sonic sculpture reaching heights which few have touched. A thing of beauty and an album as perfect as they come.

The reemergence of Motore Immobile heralds what is unquestionably one of the most important reissues of the year.

"Somewhere along the way, working on hint and clue, Giusto Pio’s Motore Immobile came back into view. This artifact - formerly lost to time, has sent countless collectors anxiously scrambling through the bins. Luck was few and far between. Initially issued by the legendary Cramps imprint in 1979, the album has remained among the most unobtainable, sought after, and cherished releases, among the label’s astounding output. Emerging for the first time on vinyl since its original pressing, it’s a day for sighs of relief.

Giusto Pio, like many in his generation of Italian musicians and composers, was restless. Trained as a classical violinist, he began his career in the orchestras of Milan, but didn’t remain long. During the late 70’s, at the encouragement of his student Franco Battiato, he delved into the world of the avant-garde. Over the following decades, Pio and Battiato formed a close collaborative relationship - chasing each other across genre and time. As Battiato entered the world of Pop music during the early 80’s - emerging as an unlikely star, Pio was behind many of his hits, sometimes flirting with equal fame. Perhaps the greatest tragedy of their most productive years - those in the spotlight, was the obscuring and loss of their most important works - the albums which first grew from the joining of their minds. As Battiato’s remarkable catalog on Ricordi and Bla Bla drifted from view, so too did Pio’s Motore Immobile.

While a towering artifact from Italy’s astounding Minimalist movement, and among the first great collaborations between Pio and Battiato, in hindsight, Motore Immobile is a symbolic death knell - a signalling of the end. It is among the last explicitly avant-garde efforts on which either would work. Change was in the wind, pushing the past from view. For decades, its obscurity has remained a haunting tragedy among fans - needling consciences - echoing from the depths - longing to be heard. While careers rose and fell, hiding in the shadows, was one of the most striking and singular masterworks of Minimalism ever composed.

Motore Immobile is an exercise in elegant restraint - note and resonance held to their most implicit need. Ringing with subtly and depth - everything between root and embellishment stripped away. A sublime organ drone, penetrated by deceptively simple structural complexity - quite interventions of Piano, Violin, and Voice. A sonic sculpture reaching heights which few have touched. A thing of beauty - as perfect as they come - singular, but not alone.

The reemergence of Motore Immobile sits within an important reappraisal of a large neglected body of efforts made by the Italian avant-garde during the second half of the 1970’s and the 80’s. This incredibly diverse movement, though among the most important of its century, was rarely heard beyond that country’s borders, and only acknowledged by a few within. Of its most striking output, Motore Immobile is among the most important to have remained hidden from view. It now joins its rightful place - resonating within a collective world of shimmering sound, one familiar to fans of Battiato, Lino Capra Vaccina, Luciano Cilio, Roberto Cacciapaglia, Francesco Messina and Raul Lovisoni. Its reissue heralds what is unquestionably one of the most important moments of the year." Bradford Bailey