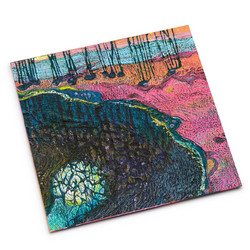

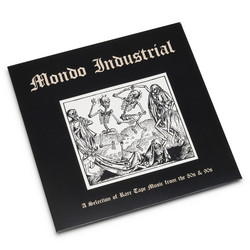

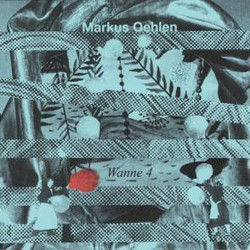

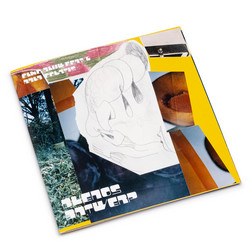

Rampe Amalgam presents Markus Oehlen not as the “neue wilde” madman of legend, but as a meticulous maximalist whose chaos is always engineered. Much as Charlemagne Palestine was tagged a minimalist only to reveal himself as a density addict, Oehlen has been caricatured as a wild punk primitive when in reality his working life runs on a strict split: painting from eight in the morning until four in the afternoon, then music from four until the neighbours intervene. That discipline, and a lifelong attraction to “change overs, turn arounds and bad taste,” underpins this album. It’s a record built from clashing textures and awkward decisions that somehow always land on their feet, shouting “yes future! 50/50!” as they go.

Since the late 1970s, Oehlen’s music has run parallel to – and sometimes straight through – his visual art career. Early on he helped wire German punk’s nervous system with bands like Mittagspause and Fehlfarben, then plunged into new/no wave turbulence alongside DAF’s Gabi Delgado in Deutschland Terzett. What followed were a string of artist records and ad‑hoc ensembles with a notorious circle of co‑conspirators: Martin Kippenberger, his brother Albert Oehlen, Jörg Immendorff, A.R. Penck, Werner Büttner, and free‑jazz heavies like Rüdiger Carl and Sven‑Åke Johansson. These projects weren’t side‑hobbies so much as another surface for Oehlen’s restless mark‑making, exchanging canvas and brush for tape, drum machine, saxophone and cheap synth.

In the early 2000s the Oehlen brothers tightened the feedback loop between painting and sound. They played together often, and spun off duos and trios that gleefully mangled genre borders: Van Oehlen, an off‑beat, Suicide‑tilted synth rock’n’roll unit that ran drum‑machine throb under deadpan vocal smears and warped keyboard hooks; Jailhouse, an “electronic free jazz” project where sax blurts, malfunctioning electronics and lopsided rhythms collided in real time. On his own, Markus has been steadily carving out a body of electronic work under his own name and as Don Hobby. Rampe Amalgam slots into that continuum: a set of tracks that treat digital and analogue sound like paint scrapings, torn posters and photocopies fed back through the machine.

The music toys with concrète in a way that invites comparison with artists like Russell Haswell or Autechre: dust, glitches and room noise erected into short‑circuiting firework displays, bursts of signal that feel both meticulously programmed and happily derailed. At the same time there’s a distant kinship with Wolfgang Voigt’s GAS project – not in any overt stylistic mimicry, but in the sense of someone smuggling rhythm into places where it’s barely allowed. Beats are often “in the next room”: muffled kicks implied by reverb tails, pulses suggested by the periodic return of a distorted sample rather than by any explicit drum track. Melodic material, when it surfaces, tends to be as battered and collaged as his visual motifs – loops that seem found rather than composed, chopped to the edge of recognition and then allowed to wobble in and out of focus.

What keeps Rampe Amalgam from collapsing into pure abstraction is Oehlen’s instinct for structure. Even the most fractured pieces trace arcs: accumulations of sonic junk that suddenly thin into a single, insistent tone; stretches of near‑beat that never quite resolve into a groove before being undercut by a new layer of interference; fade‑outs that feel like the listener being shoved out of the studio rather than a polite goodbye. It’s music that shares a sensibility with his paintings and collages: dense, irreverent, clowning and menacing at once, but always balanced by an underlying compositional spine.

He may have been introduced to the world as a punk pioneer and visual provocateur, but Rampe Amalgam shows Markus Oehlen as something more intricate: a day‑long worker who lets the habits of the painting studio bleed into the sequencer, and who understands that the most effective disruption is the kind that’s planned with care and executed with a perfectly crooked grin.