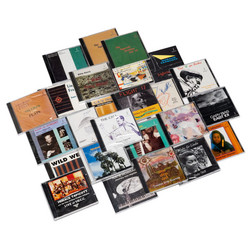

Tip! One of the first Irida releases, Texas Music (IRIDA 0026, 1979), collects compositions by Jerry Hunt (hailing from Dallas), Philip Krumm (based in San Antonio), and Jerry Willingham (“in and out” of Austin). The record was produced in two editions: one for mass consumption in a corrugated plain brown sleeve featuring a single fish stamp on the cover by the artist David McManaway, and a small “fundraising edition” sold in the same packaging at a higher price with a numbered print by McManaway. The original album features unattributed liner notes, clearly written by Hunt in his logorrheic style, giving a curatorial spin to his colleagues’ compositions. Focused on their structural and technical arrangements, Hunt’s comments only heighten what music critic Peter Rabinowitz would call the “stern and unapproachable” nature of the music.

Hunt’s contribution to the album, “Lattice” (1978–79), is his only composition specifically for solo piano. A virtuosic pianist himself, Hunt had labored over his own attempt to write for the instrument but was dissatisfied with its limited ability “to be tuned,” as he said—one assumes tuned in unconventional ways—and its “lack of response” (i.e., attack). Hunt based the composition on the geometric principles of the lattice. The resulting score was game-like and theatrical in a manner that would come to characterize his later solo performances sans piano. To further circumvent the perceived limitations of the instrument, Hunt produced a “gestural blanket,” both sonic and visual, by attaching small metal objects and bells to the performer’s wrists and ankles. As he states in the original liner notes to Texas Music, “‘Lattice’ was devised in 1978 to allow insertion of invariant intonation-timbre features into the melody-rhythm pattern requirements of a variable intonation-timbre structure.” That is, Hunt added extra-instrumental sounds—the small noises created by the metal objects attached to the pianist, which are activated by the player’s movements—to alter the listener’s perception of the piano’s tonal and timbral qualities, an effect accentuated by the piece’s melody and rhythm. In a radio interview with Charles Amirkhanian, Hunt assured the listener that the piano was not prepared and that there was “no funny stuff inside.” According to Hunt’s instructions, each performance of “Lattice” should be adaptable to the architecture and resonance of the room. As with many of his compositions, the score consisted of a set of parameters and suggestive language that described possibilities for the performance; many details were left up to the interpreter, who was, in nearly all cases, Hunt himself.

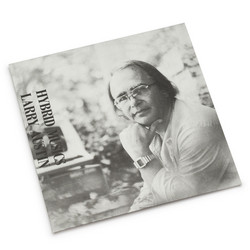

Philip Krumm, Hunt’s friend and collaborator, had incredible access to notable experimental music figures of the time, including John Cage, with whom Krumm initiated a correspondence after reading an article on the elder composer in a 1959 issue of Time magazine. Krumm’s composition on Texas Music, “Sound Machine,” premiered at the University of California, Davis, in 1966, where it was performed by the New Music Ensemble, which included Larry Austin’s students Dary John Mizelle, Art and Pat Woodbury, and a handful of other musicians. The graphic score for “Sound Machine” is a variable piece that can be arranged in a number of different ways for either solo performer or ensemble situations. Individual pages of the score can be treated as separate compositions to be performed on their own, simultaneously or sequentially with the other pages. The version included on the record is an interpretation based on live recordings that Hunt and Krumm had made in the early ’70s with clarinetist Houston Higgins and soprano vocalist Jill Higgins. Hunt applied his own processes to the piece, and further manipulated samples from these recordings using a small digital recording system, creating what Krumm describes as an essentially electronic interpretation of his score.

Jerry Willingham, a native Texan and classical flutist, had developed an interest in experimental composition through his involvement with multimedia events and collaborations with dancers and writers in Austin, where he resided in an abandoned house of worship turned performance venue known as the chURch. Hunt shared Willingham’s interest in dance; he had served as the music director for dancer Toni Beck in the late ’60s and early ’70s and had orchestrated and participated in a number of intermedia events through the rest of the ’70s. Hunt took an interest in his fellow Texan’s music too, and encouraged Willingham to revisit his 1974 composition “Ta Ch’u” for Texas Music— its name a reference to the twenty-sixth hexagram of the I Ching (a favorite aleatoric compositional device employed by Cage), which alludes to controlled power and amplification. Willingham’s interpretation was written for any arrangement of wind and percussion; it is modular and indeterminate, requiring the interpreters to contribute a great deal to the work through their own decisions about its performance.