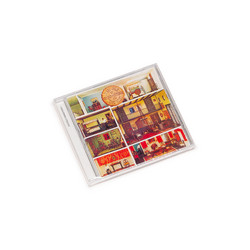

New York avant-garde luminary Joe Byrd had been the leader of pioneering ’60s electronica band The United States of America until given the heave-ho by his own creation. His riposte was to create this in turns beguiling and bizarre album, which if anything is even further out on a limb than his previous band’s sole groundbreaking LP. While obviously a ’60s sounding record, its many unexpected twists and turns along with Byrd’s stunning production leave it sounding undated, existing parallel to its time in its own peculiarly twisted universe, all of which is testament to Byrd’s and his new bandmates’ creativity. Taking in Jefferson Airplane-tinged psych-pop along with influence from other lysergically assisted West Coast bands of the time, adding skewed observations of traditional American music such as ragtime and vaudeville, Byrd filters it all through experimental electronica, tape loops and early use of the synthesiser that gives its ’60s groove a decidedly off-kilter feel, as if one is a passive observer of a music hall performance set in a trendy kaleidoscopic discotheque as seen through a hall of mirrors. Imagine tripping while listening to the Great American Songbook played by tiny dancing bellboys, and you might have an idea.

The songs hidden within are gems, and The United States of America’s radicalism is continued in these lyrics, which savage various aspects of the American Dream. The most scything of these comes with Leisure World, pronounced “Leezure” as is the American way, which somehow makes the voiceover advertising spiel for the titular Californian retirement community sound even more insidiously evil than it has any right to. I won’t spoil the fun, but suffice to say the ending is probably best not listened to whilst eating or drinking! The three opening tracks comprise The Sub-Sylvian Litanies, a perfect musical narration for a full-blown LSD excursion if ever there was one. The synth work may sound somewhat primitive now, but one can imagine how groundbreaking this sounded at the time when combined with the tape loops and found sounds being manipulated in tandem. When You Can’t Ever Come Down kicks in with its “Waiting to die, waiting to die, waiting to die, for the 17th time” and with its grungy acid rock we’re back on more familiar ground, but the fun continues apace with the concluding woozy hymnal.

The Field Hippies were a collection of top West Coast studio musicians, some from more studious musical callings than pop or rock, and Byrd had studied under John Cage, leading to the album being originally released on Columbia’s “serious music” imprint Masterworks. For all that, The American Metaphysical Circus is a highly entertaining record, and Byrd’s intricate but never overwhelming production is key to the enjoyable listening experience. Joe Byrd is not one to hold back on his opinions, and thinks that the ’60s “wall of sound” production technique was “...awful, ending up with a mush that had neither majesty nor focus”, a trap The Beatles only avoided, according to Joe, thanks To George Martin, and one which swallowed The Beach Boys whole.

“This is not to say I think we were better than either band” he adds as an unconvincing disclaimer. Love it! Zappa also comes under Joe’s scrutiny, as it has been suggested that his scathing lyrical approach was similar to Uncle Frank’s, whom, according to our hero, “chose easy targets” (true), adding that Zappa “...didn’t think much of me either, by the way”. The American Metaphysical Circus fully deserves its place as one of the most respected artefacts of its era, and has been highly influential on subsequent production techniques and arrangements, as well as being instrumental in placing the synthesiser as a “rock” instrument. I can now see were the fabulously odd Kramer of Bongwater fame got some of his ideas from, and that’s just one example. - Roger Trenwith