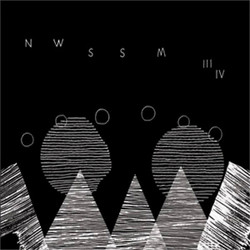

AMM and their CDs have an almost comfortable familiarity. The trio's personnel has remained fundamentally the same since the early '80s when pianist John Tilbury joined the remaining founders, drummer Eddie Prévost and guitarist Keith Rowe. Every two or three years they release a CD, usually a single uninterrupted improvisation, about an hour in length, taped in performance. The only way in which these two CDs tamper with that practice is that they were both released in 2001. 'Tunes Without Measure' 'was recorded at Glasgow's free radiCCAls festival in May 2000 ; 'Fine' a year later at France's Musique Action festival. It takes its name from the dancer Fine Kwiatkowski, a silent partner in the performance.

'Tunes Without Measure' is a slowly unfolding dreamscape in which the group attenuates both time and space. In this specific performance, Tilbury and Rowe represent very different sonic vocabularies. Tilbury delights in the acoustic resonance of a good piano, in the clearly articulated tone or cluster. His sounds hang in the air in a way that seems traditionally beautiful. Rowe's fundamental sounds are abrasive metallic ratchetings, humming feedback, treble-loaded pings and bowed guitar that might be attached to nerve ends. And always the presence of his transistor radio, ready to intrude momentarily the outside world in its worst light — "Sushi isn't just for fish!" is this day's clearest message. But together AMM create a sonic space so large here, so fundamentally clear, that there's room for the two approaches to co-exist, as if Rowe and Tilbury sometimes played at opposite ends of the universe. That expansive space is a genuinely collective creation, one that seems to draw on the audience's attention for some of its capacity. It's absurd to point out highlights in work at once as diverse and unified as this, but the combination of sonically distinct, sustained tones from the three musicians in "Tune Two" and Tilbury's lullaby-like playing in the closing "Tune Six" are especially beautiful.

While 'Fine's' opening percussion might suggest that the same ritual is about to be enacted, its first "segment" describes an utterly different world — mechanical, harsh, a world that Tilbury's piano enters warily at first before his metallic string-sweeps arise to complement the maze of feedback electronics and percussion. This world of difference between the two pieces demonstrates how far the AMM improvisation is from conventional ceremony. If it is, in a sense, a ritual of reintegration — of self, community, the senses — then it appears to work only the same way once. That is, it is a process that demands originality, a unique responsiveness to the day's possibilities. It's testimony to AMM's creativity that not only do these performances sound (and ultimately feel) utterly unalike, but either performance sounds different with each new hearing.

Stuart Broomer

Coda July/August 2002