1

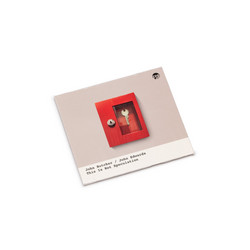

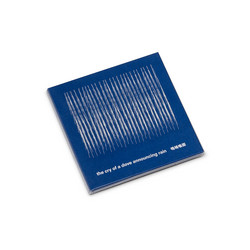

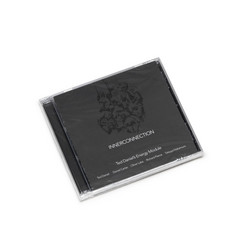

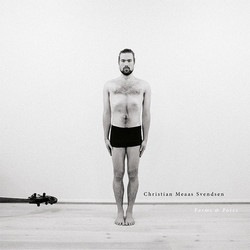

The amorphous unit that is AMM has been refining—and indeed redefining—a sound for as long as it's been in existence, and there's no reason to believe that the process this implies is likely to ever stop evolving. This does of course render John Butcher's presence here as perhaps anomalous, but there are no musical reasons to believe that this was the case in reality. The resulting trio—indeed the Trinity—of Butcher on tenor and soprano saxophones, pianist John Tilbury and percussionist

Eddie Prevost, is proven in the business of fashioning music out of nothing other than the moment, and the ability to interact—which is a shared human characteristic. The moments caught for posterity here amount to almost seventy minutes, and often they're marked by Tilbury's singular approach to the keyboard. For him, nothing is in the way of grand gesture. Instead, his approach is informed to an acute degree by touch. He ploughs what sounds like the loneliest furrow on "Meantime," while Butcher's deployment of long tones lends the music an astringent air, as if the trio is intent on doing no more than toying with the very idea of musical development. However, any tentativeness that might be implied exists only in implication. When the music stops, as it sometimes does, it's always at what seems like some point inscrutable to everyone apart from the three performers. If that implies a form of highly individual logic, then this could be the very thing that informs "Flamsteed." Of course, it's the case that Butcher has long since attained his own vocabulary in his chosen field of musical endeavor, and here he deploys it as tellingly as he does anywhere on this set. He sometimes sounds as though he's in thrall to the silence, though not to the point at which nothing needs to be said. He is, however, exceedingly careful in how he puts it to use, like a speaker for whom spoken words are things that can never be measured enough. Prevost exploits the silence in a quite dissimilar way, and the same is true of Tilbury in his use of the piano's conventional vocabulary. The resulting music is rarefied, though not to the point at which the listener is alienated from proceedings. In its very lack of both volume and overt rhetoric, this is enticing music that perhaps coaxes the exploration of new vistas, the exploration of which make Trinity a privilege to experience. (Nic Jones, AllAboutJazz)

Details

Cat. number: MRCD71

Year: 2008