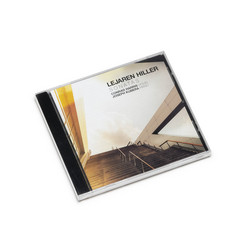

William Sharp, Steven Blier, Virgil Thomson, Paul Bowles, Lee Hoiby, Richard Hundley, John Musto, Eric Klein (5)

Works by Thomson, Bowles, Hoiby, Hundley, Musto and Klein (CD)

American art song has traveled a long way from the parlors of 19th-century America. The turn of this century brought its adolescent rebellion in the iconoclastic hands of Charles Ives, followed by an impressive, if somewhat retrospective, era heralded by such composers as Bacon, Chanler, Nordoff, and early Thomson. But by mid-century, what should have been a time of full adulthood was instead a curiously fallow period (which Philip L. Miller attributes to composers abandoning melody and Ned Rorem attributes to singers, audiences, and benefactors abandoning the recital).

In the melting pot of 20th-century America composers have chosen many different paths, searching out inspiration in their European antecedents, American ancestors, New World folklore, jazz, and even the exotic East; they have tried a multiplicity of styles, from neoclassicism to atonality, from post-romanticism to dodecaphony. Ruth C. Friedberg, in her perceptive three-volume study American Art Song and American Poetry, observes that despite this eclecticism, three common elements permeate the American song: the endeavor to create the sound and feel of American speech (in all its permutations); the search for a new, uniquely American spiritual order; and, perhaps most strikingly, an impulse toward simplicity. Exercising what Friedberg call this "national artistic urge to cut away the dead wood," many of our finest lyric composers have found that all roads lead to the same place: the "mainstream" American art song, a self-contained piano-vocal work that strives to communicate the emotional life of a poem.

It is this discovery that has undoubtedly led to the current flowering of American art song. In the 1980s, the elder statesmen among our composers are finally coming into their own, and fresh young composers are emerging. Thus, this album is more than a sampling of the American art song: it is a testament to its good health.