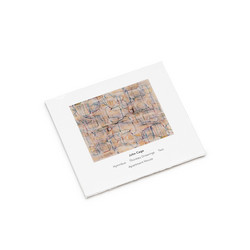

"The Solo for Piano is part of the legendary Concert for Piano and Orchestra. It is an indeterminate work, consisting of 63 pages made of 84 different types of composition, each appearing as its own type of notation. The performer creates his own performance by choosing which pages to play and in which order; pages can also be omitted. John Cage began by choosing, using chance operations, a way of composing based on either his Music for Piano series – single notes, or on Winter Music – chords, or aggregates of notes. Chance operations would also determine whether a variation on one of these two types would be used or whether something completely new, with its own subsequent variations, would be written.

When Cage wrote the Two Pieces for Piano (1935), he was already studying with Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s influence on Cage undoubtedly accounts for the music’s 12-tone-row-based organization, but Cage’s own version of this system had the twelve note series broken down into short pitch / rhythm cells.

Later Cage began a study of Indian philosophy and came to believe that the purpose of music is “to imitate nature in its manner of operation” and “to sober and quiet the mind thus rendering it susceptible to divine influences.” These principles underlie another set of piano pieces that Cage wrote in the months May to August, 1946, entitled again, Two Pieces for Piano (1946). These later pieces are more extensively worked out and possess a sense of urgency and height- ened drama, brought about in the first piece by long silences and in the second by a quicker flow and variety of musical events distributed over a greater range of the instrument. The silences heard in the first piece are an early example of what later became a pillar of Cage’s thought and music — the primacy of silence.

In the 1980s Cage planned a set of pieces to be called Sports, based on Satie’s set of pieces for piano, Sports et Divertissements. Only two were completed — Perpetual Tango in 1984 (recorded on Mode 31 by Haydée Schvartz), and Swinging in 1989, which is modeled on the second piece in Satie’s set, La Balançoire. Satie’s left hand accompaniment, swinging back and forth across a melody played by the right hand, is still present in Cage’s piece, but Cage has re-fashioned the original melody, mostly lengthening durations. The player is given a range of pitches from which to choose for both right and left hands."