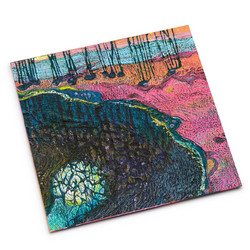

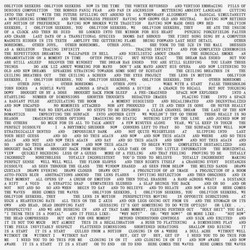

Factitious Airs (Electronic Music) presents Robert Worby as a kind of forensic poet of recorded sound, reanimating the classic tape‑music ethos with digital tools while refusing any hint of retro cosplay. Across pieces like “Stumble Bum Junk Heap,” “Cody’s Receiver,” “To Come Speedy Upon Them” and “The Blind Momentum of Catastrophe,” he works not with synthetic grand gestures but with minute, often easily overlooked acoustic events, folding them into intricate structures where what initially seems insignificant gradually becomes decisive. The album is explicitly “about recorded sound and structures made with recorded sound,” and it clings to that focus with almost ascetic discipline.

Worby treats the question of source as a red herring. How a sound was produced, or which object made it, is declared “of secondary interest”; what matters is the grain, the envelope, the internal life of the noise itself. Tiny clicks, air rushes, tape bumps, muffled thuds and fragmentary tones are isolated, looped, stretched and layered until they form coherent but ambiguous patterns, like close-up photographs of textures whose larger context has been deliberately cropped away. Acute, obsessive listening pulls these particles into focus: what might at first register as static or “nothing happening” slowly reveals rhythmic filigree, beating harmonics, or ghostly melodic motion.

The four main works each explore a slightly different angle on this material thinking. “Stumble Bum Junk Heap” feels like an animated scrap yard, all analogue wobbles, sudden suck‑ins of air and clattering debris that assemble into lopsided but compelling pulses. “Cody’s Receiver” drifts toward the radiophonic, its sine waves and harmonics brushing against heavily processed library‑style sound effects, as if tuning across stations that bleed into one another. “To Come Speedy Upon Them” tightens the screws, using patterned bursts and off‑kilter pulses to generate a nervous forward motion that’s more psychological than metric, while “The Blind Momentum of Catastrophe” lives up to its title with accumulating layers of motion that threaten to tip into overload without ever quite doing so.

Underlying these pieces is a compositional attitude described as curiosity pushed to the point of compulsion. Inspiration might arise from “a tiny detail” in another work, or from the wider “history of ideas” rather than from sound alone; once seized, that detail is subjected to close examination and transformation until it becomes the seed of an entire piece. Meaning, in this framework, is emergent rather than imposed: as Worby builds his structures, associations flicker into being - with images, narratives, objects, situations - but remain “highly subjective, ambiguous and uncertain,” never locked down into programmatic stories. The music’s refusal to stabilise its metaphors is part of its charge: listeners are constantly nudged into making and remaking their own sense of what they’re hearing.

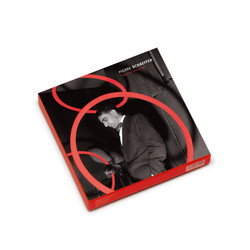

One striking aspect of Factitious Airs is how it sits in time. As Carl Stone notes, there’s an uncanny quality to the way Worby uses contemporary digital production to evoke the aura of the 1950s and ’60s radio studios where Stockhausen, Pierre Henry and Berio forged early electronic and tape music, while still sounding “bright and fresh” to modern ears. Analogue‑style warble, tape‑like saturation and radiophonic spectrality are present, but they’re handled with a lightness and clarity that avoids pastiche; instead, the album feels like a parallel present in which that early studio culture never ossified into museum status. For listeners attuned to electroacoustic detail, Factitious Airs (Electronic Music) offers a compelling invitation to listen closer, to treat every scrape and shimmer as a potential protagonist in its own quietly unfolding drama.