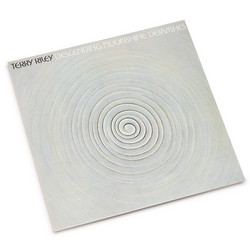

Terry Riley

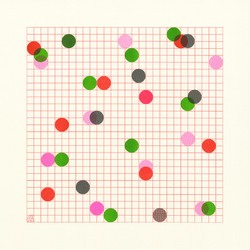

A Rainbow In Curved Air (LP, Coloured)

• Limited edition of 750 numbered copies on yellow vinyl. 180 gram audiophile vinyl • In the pantheon of American experimental music, few works possess the historical gravitas and enduring influence of Terry Riley's A Rainbow in Curved Air, released in 1969 on CBS Records' short-lived "Music of Our Time" series. This album represents nothing less than a seismic shift in the trajectory of Western art music, establishing compositional and technological precedents that would reverberate through five decades of electronic music evolution. The work stands as a singular achievement in the synthesis of Eastern modal philosophy with Western technological innovation, creating what can only be described as a new ontological framework for musical experience.

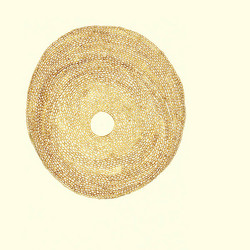

The album's title composition, occupying the entirety of side one, demonstrates the composer's revolutionary approach to temporal organization through what he termed "time-lag accumulator technique." Employing multiple tape recorders in feedback loops, Riley created an acoustic palimpsest where melodic fragments echo, overlap, and gradually transform, generating a musical architecture that exists in perpetual flux. The composer performs all instrumentation himself—electric organ, two electric harpsichords (including the distinctive RMI Rock-Si-Chord), dumbec, and tambourine—yet through his pioneering overdubbing methodology, achieves a density of texture that suggests an entire ensemble locked in mathematical precision. The harmonic language draws explicitly from Hindustani classical music, particularly the concept of raga as both melodic framework and spiritual discipline. Riley's extensive studies with Pandit Pran Nath informed his understanding of microtonal inflection and cyclical form, elements that permeate every phrase of A Rainbow in Curved Air. The work unfolds through modal territories that eschew Western functional harmony in favor of what ethnomusicologist Robert Christgau would later identify as "ecstatic stasis"—a state where forward momentum and meditative suspension achieve perfect equilibrium.

The B-side composition, Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band, represents an equally radical departure, prefiguring the ambient music movement by nearly a decade. Here, Riley's soprano saxophone becomes the primary vehicle for extended melodic lines that stretch across the temporal canvas like calligraphy in slow motion. The "Phantom Band" of the title refers to the tape-delayed echoes that create ghostly doubles of each phrase, a technique that Brian Eno would later acknowledge as foundational to his own ambient experiments. The work's employment of jump cuts and tape manipulation techniques directly anticipates the sampling methodologies that would define hip-hop and electronic dance music decades later. From a purely technical standpoint, A Rainbow in Curved Air represents one of the earliest multitrack recordings to fully exploit the artistic possibilities of the medium. David Behrman, the CBS Records editor who facilitated the album's production, recognized that Riley was not merely using technology as a tool but was fundamentally reimagining the relationship between performer, composition, and recording apparatus. The studio becomes a compositional instrument in its own right, a concept that would prove prophetic in the age of digital music production.

The album's influence on subsequent musical developments cannot be overstated. Pete Townshend's acknowledgment that Baba O'Riley and Won't Get Fooled Again were directly inspired by the composer's work represents merely the most visible manifestation of the album's impact on rock music. The German electronic pioneers Klaus Schulze, Edgar Froese, and Kraftwerk all cited A Rainbow in Curved Air as a formative influence, while Giorgio Moroder's disco innovations and the entire trajectory of ambient music can be traced back to Riley's template. Even Miles Davis's electric period, particularly the Get Up with It sessions, bears the clear imprint of these temporal experiments. Contemporary critical reception has only intensified the album's canonical status. With progressive rock authorities awarding it a 4.38/5 rating and 46% of critics designating it an "essential masterpiece," the work continues to generate the kind of sustained analytical attention typically reserved for acknowledged classics. Critics consistently note its paradoxical nature: simultaneously of its time and timeless, technological yet organic, structured yet improvisational. This dialectical quality reflects Riley's sophisticated understanding that true innovation emerges not from wholesale rejection of tradition but from the creative synthesis of seemingly incompatible elements.

The album's position within the broader context of American minimalism deserves particular attention. Where Steve Reich explored phasing and Philip Glass developed additive processes, Riley pioneered what might be termed "accumulative minimalism"—a technique where repetitive patterns generate complexity through layering and temporal displacement rather than linear development. This approach would prove particularly influential on electronic music producers, who recognized in the composer's methodology a blueprint for the loop-based composition that defines contemporary dance music.

A Rainbow in Curved Air also represents a crucial document in the history of countercultural aesthetics. The composer's liner notes, with their vision of a transformed society where "the concept of work was forgotten" and the Pentagon is "painted purple, yellow & green," articulate the utopian aspirations of the 1960s avant-garde. Yet the music itself transcends its historical moment through its rigorous formal construction and spiritual depth, qualities that ensure its continued relevance in an increasingly fragmented cultural landscape. The work's technical innovations in tape manipulation and multitracking established precedents that would define electronic music production for decades to come. Bill Laswell's later integration of dub techniques with avant-garde composition, the emergence of ambient house in the 1990s, and the contemporary revival of modular synthesis all trace their lineage back to these pioneering experiments. The album's influence extends beyond music into sound design, installation art, and even meditation practices, testament to its fundamental reimagining of what musical experience can encompass. In assessing A Rainbow in Curved Air from the perspective of five decades of musical evolution, its status as a landmark achievement becomes even more pronounced. The album succeeded in creating a new musical language that was simultaneously radical and accessible, experimental and emotionally engaging. It demonstrated that technological innovation could serve spiritual and aesthetic ends rather than mere novelty, a lesson that remains vitally relevant in our current moment of digital saturation. Terry Riley accomplished nothing less than the expansion of musical consciousness itself, creating a work that continues to reveal new possibilities with each encounter. This is the mark of truly great art: its capacity to remain perpetually contemporary while serving as a bridge between past wisdom and future possibility.